Susanna Edwards interviews Angharad Lewis looking at ‘Content Review – Editing and Reflection’

Angharad Lewis is currently head of visual communication at the Cass School of Art, Architecture and Design, where she has been working as a lecturer for a few years. She also worked as a writer and editor in the design worlds for a number of years. She authored books and contributed to various journals and magazines. Angharad didn’t study graphic design, she studied English literature and History of Art for her undergraduate degree. That was a combined degree. she was really interested in Fine Arts but also loved writing so that’s why I chose that double honours degree in two subject areas.

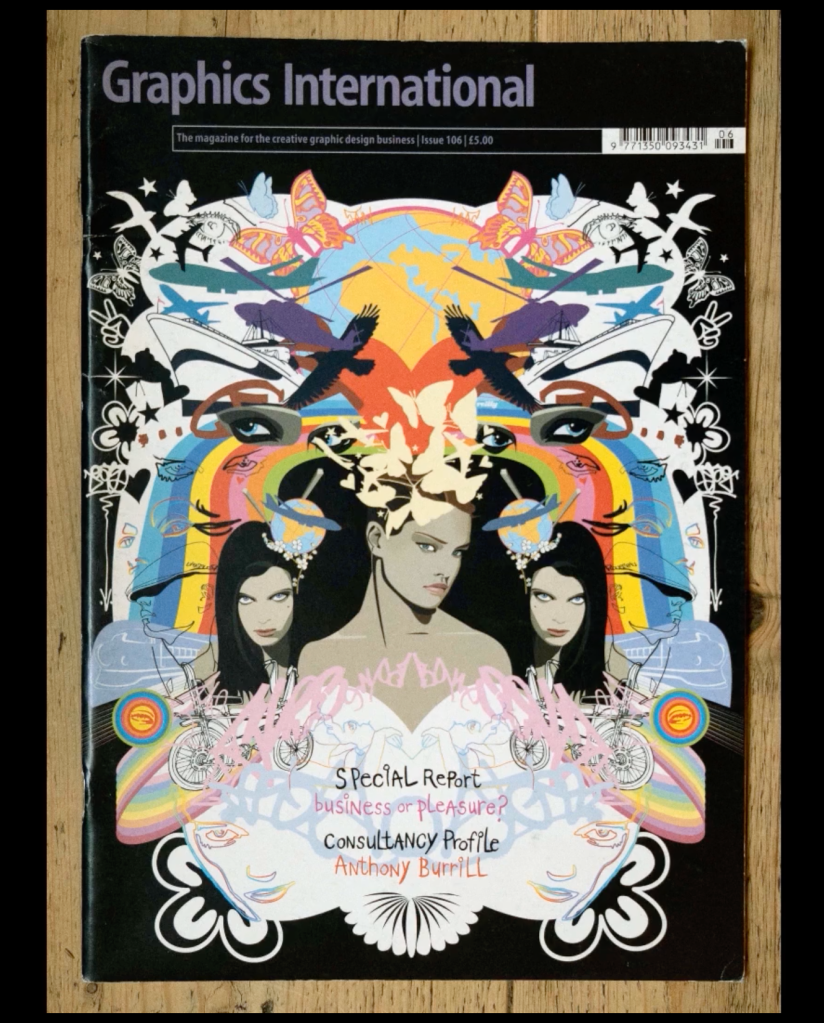

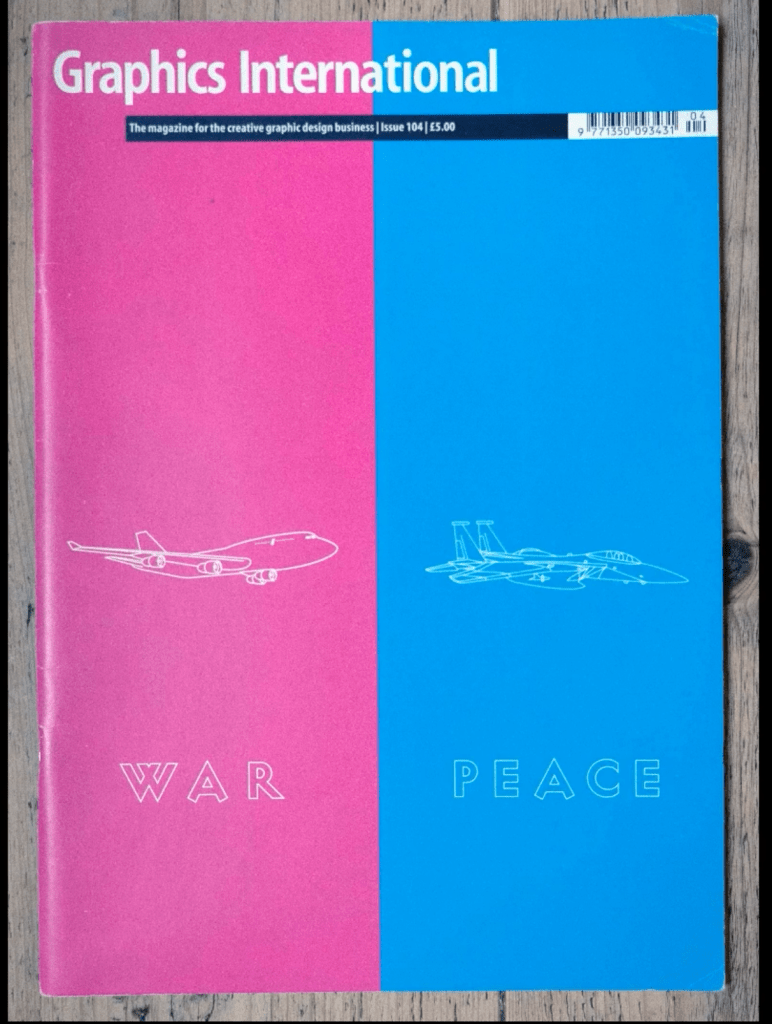

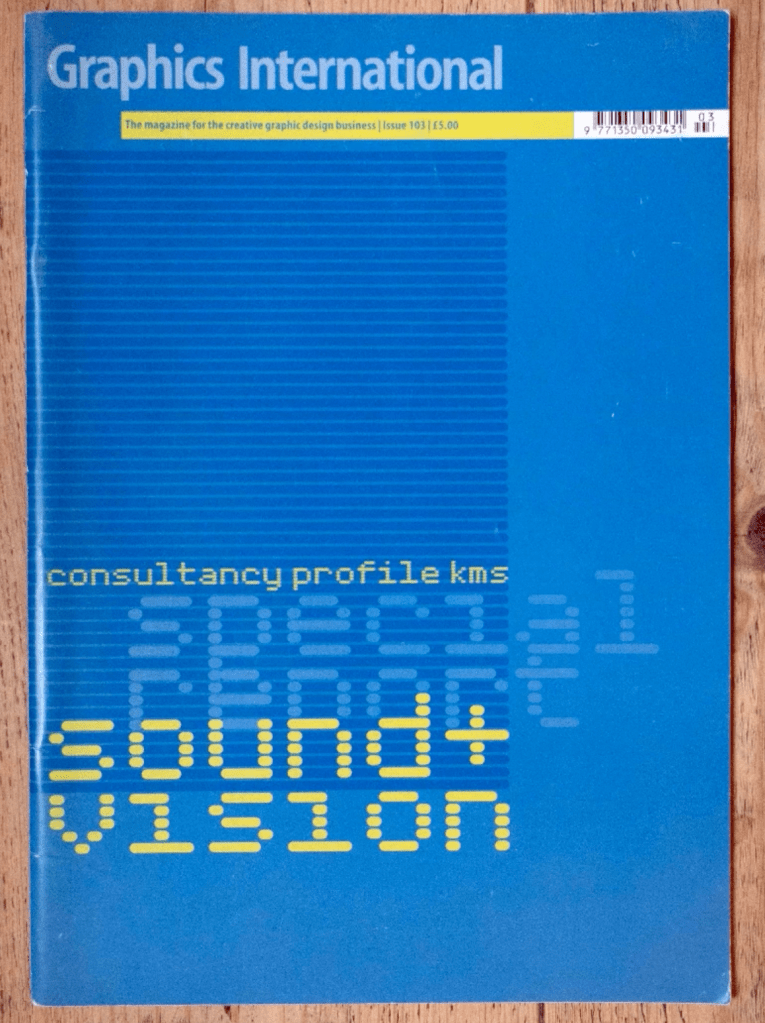

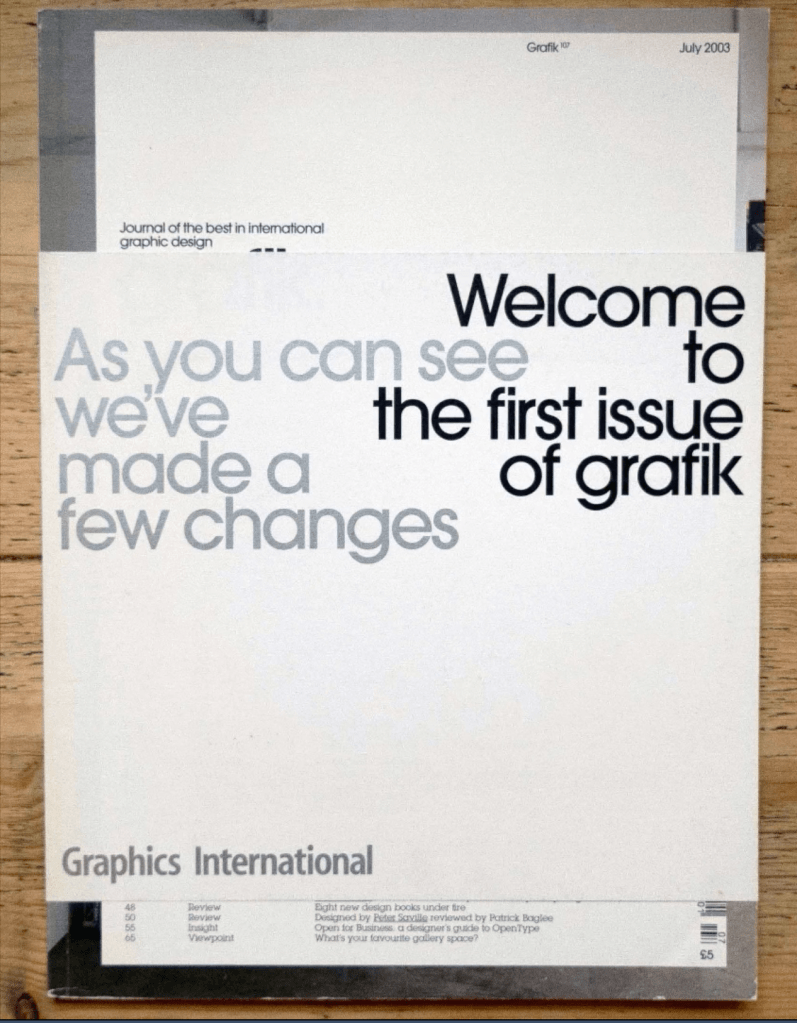

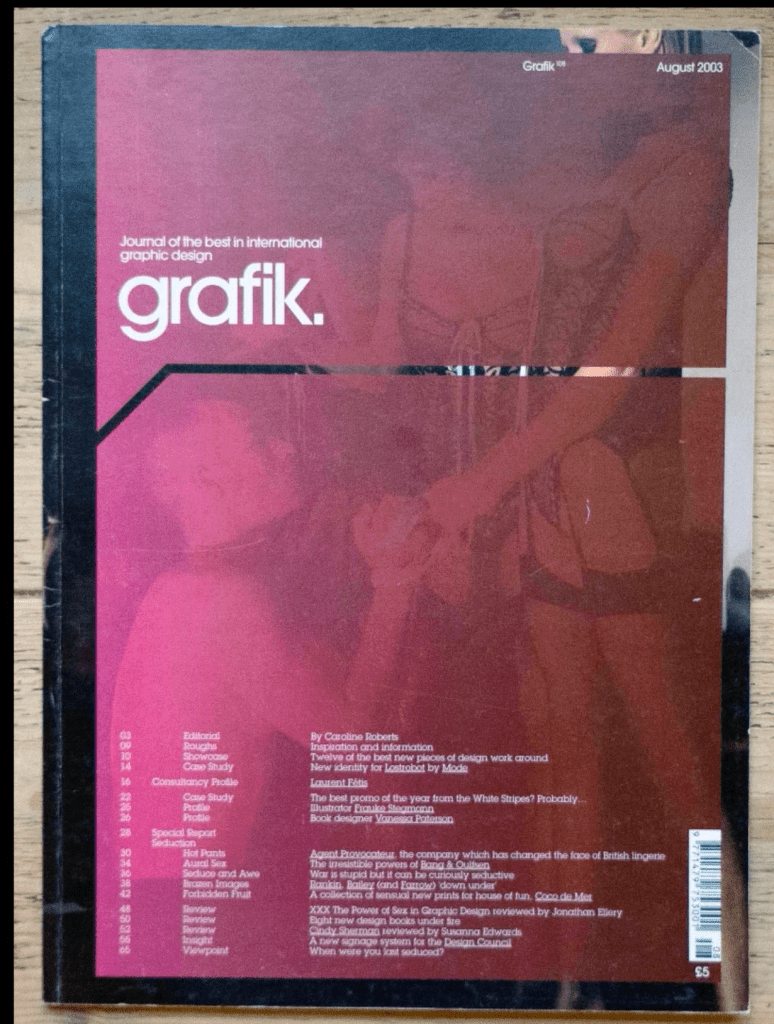

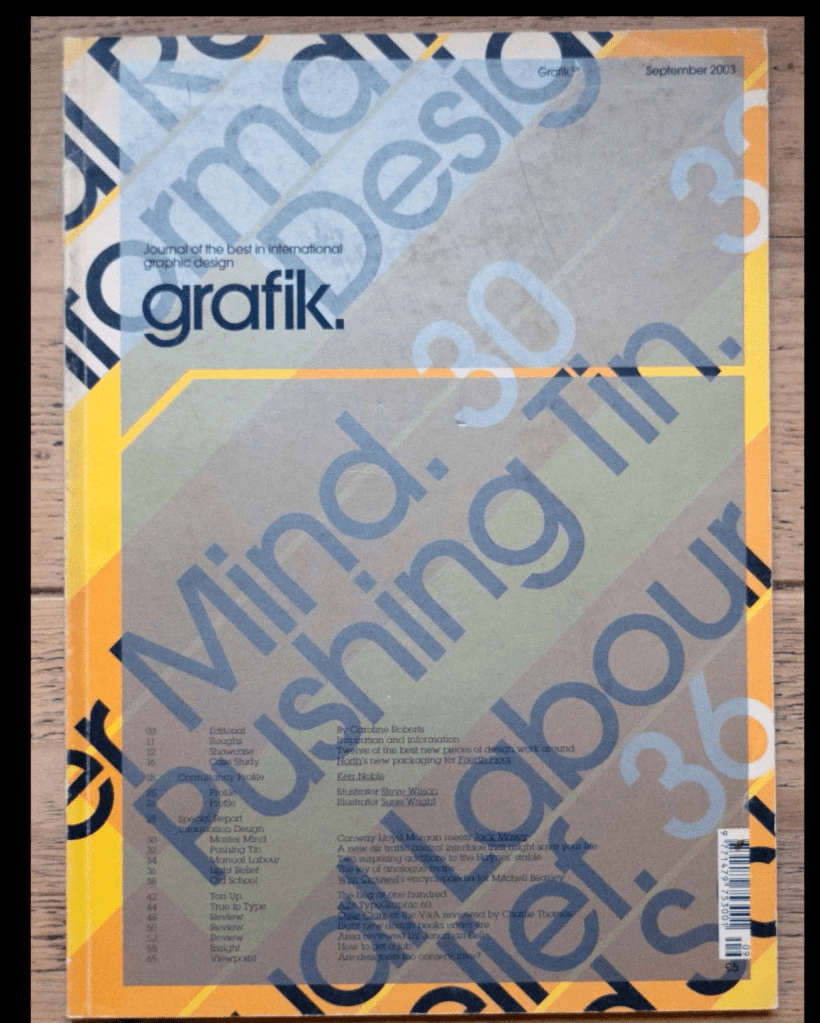

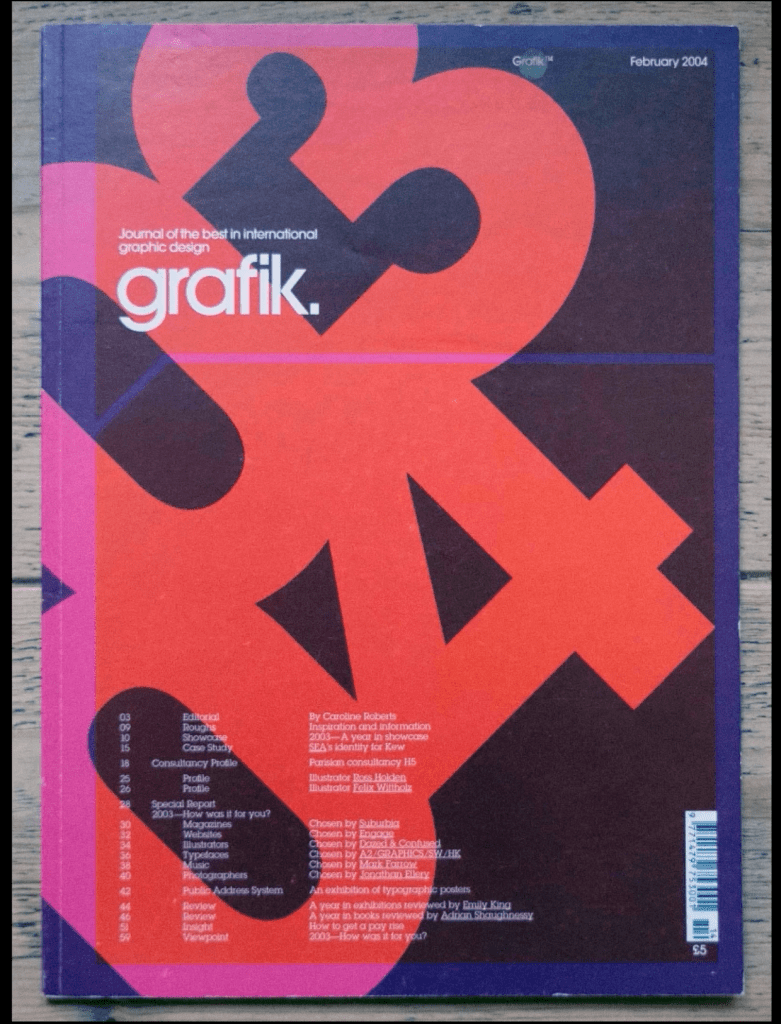

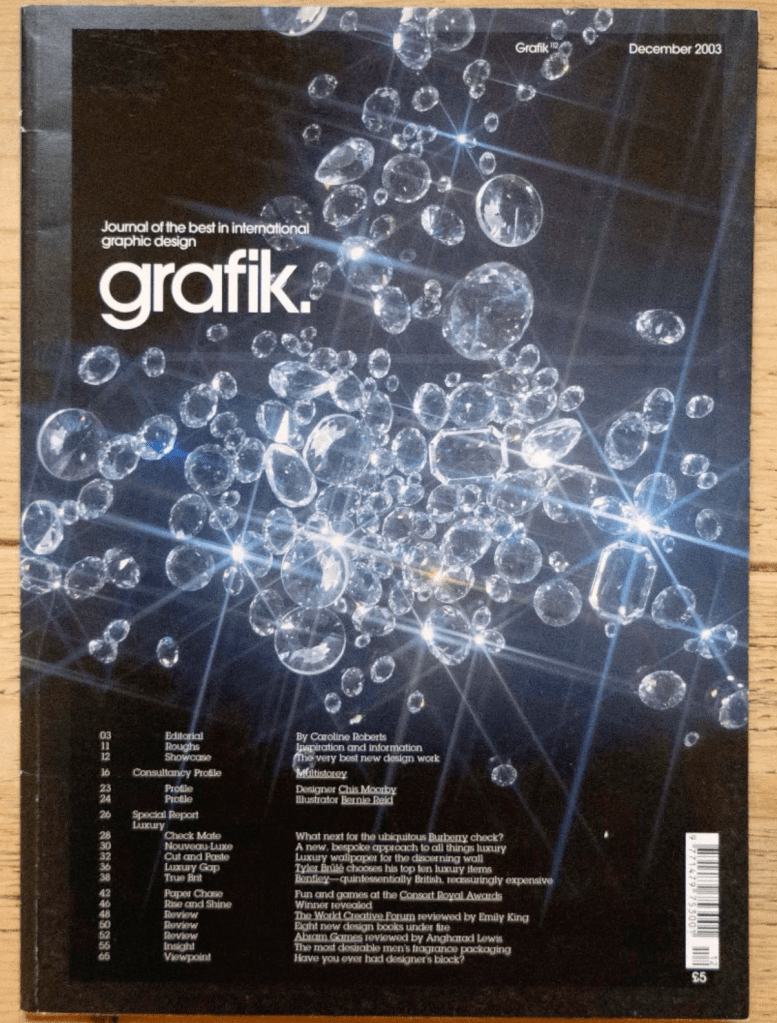

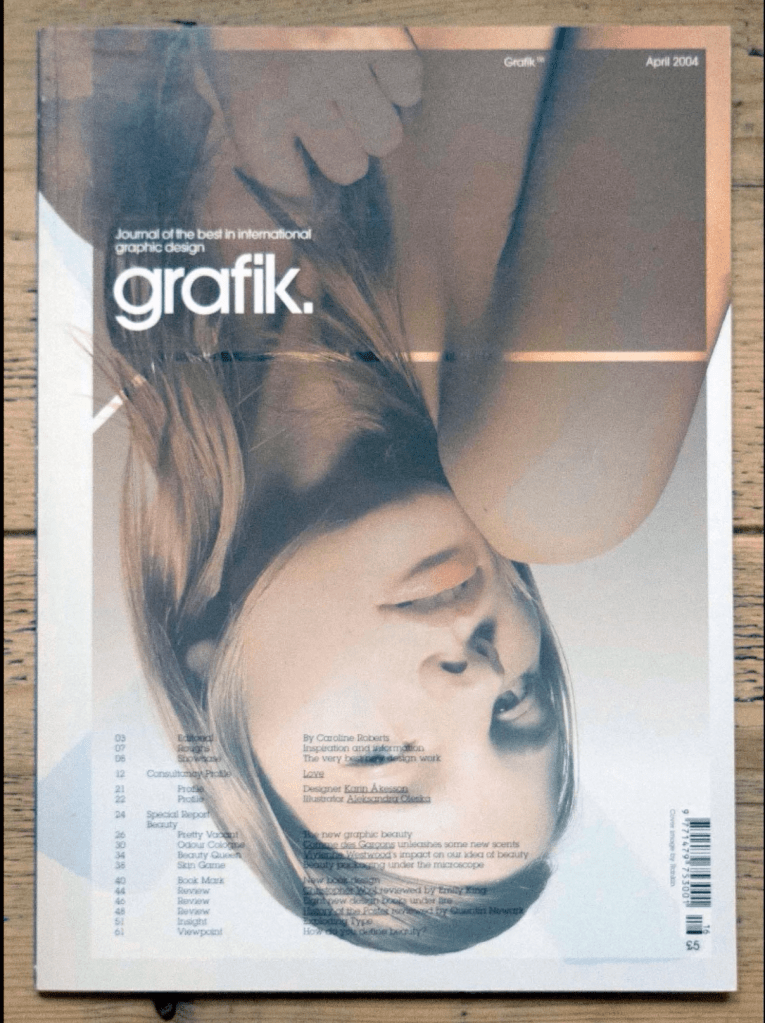

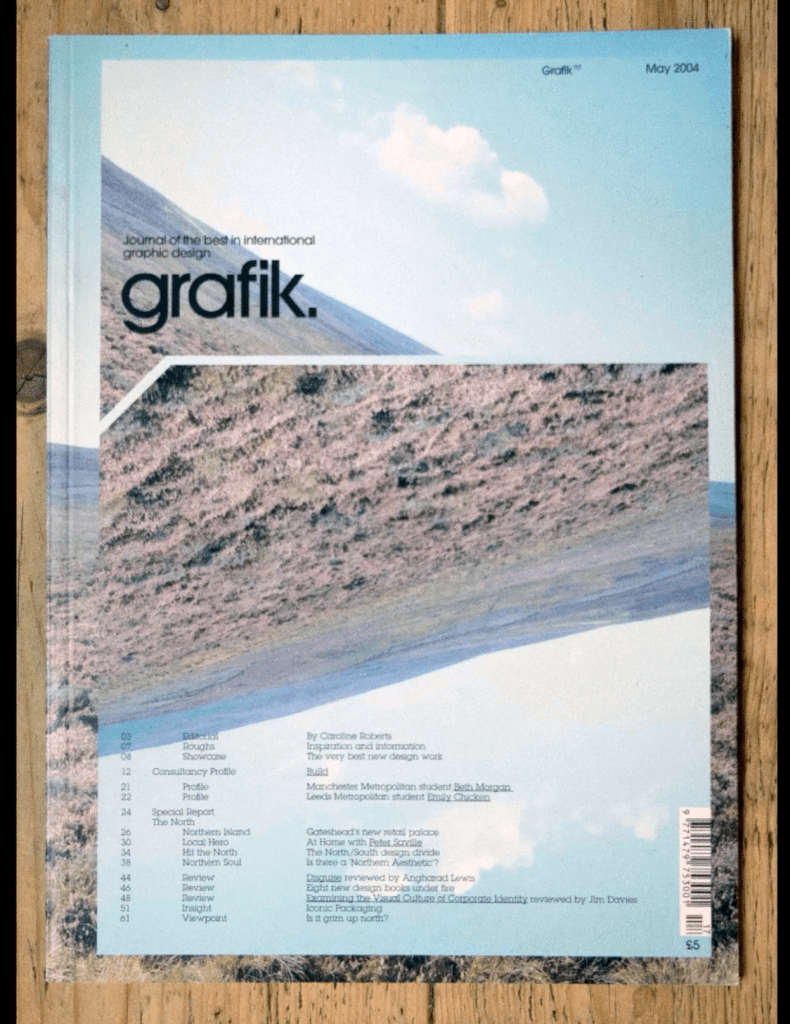

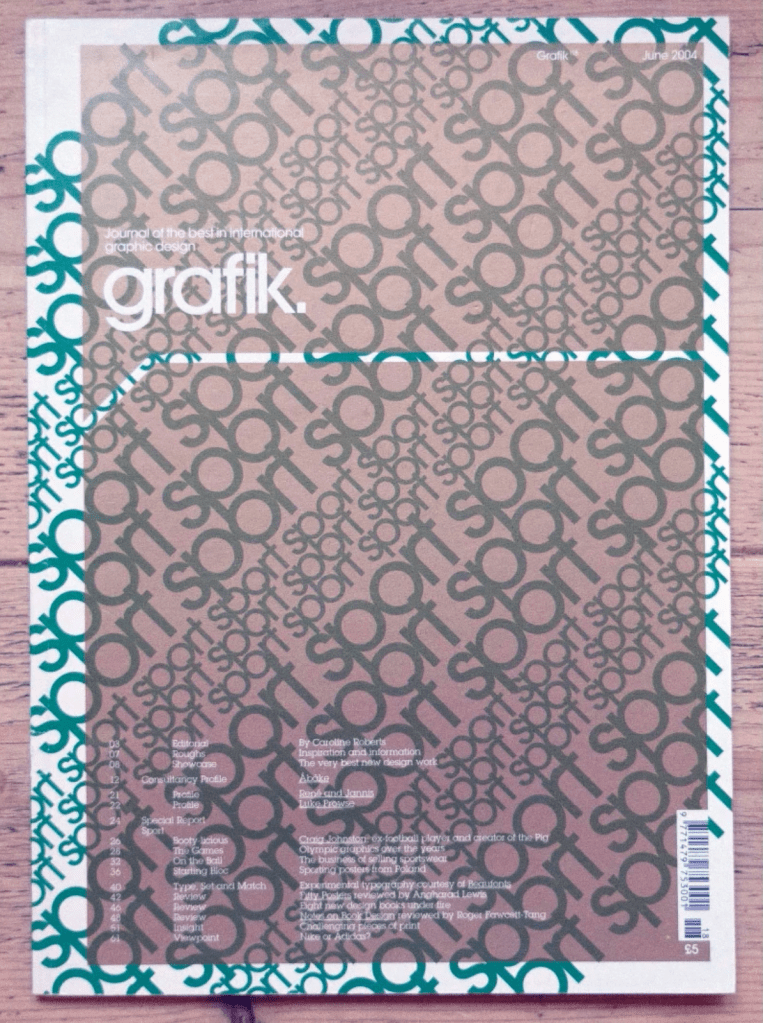

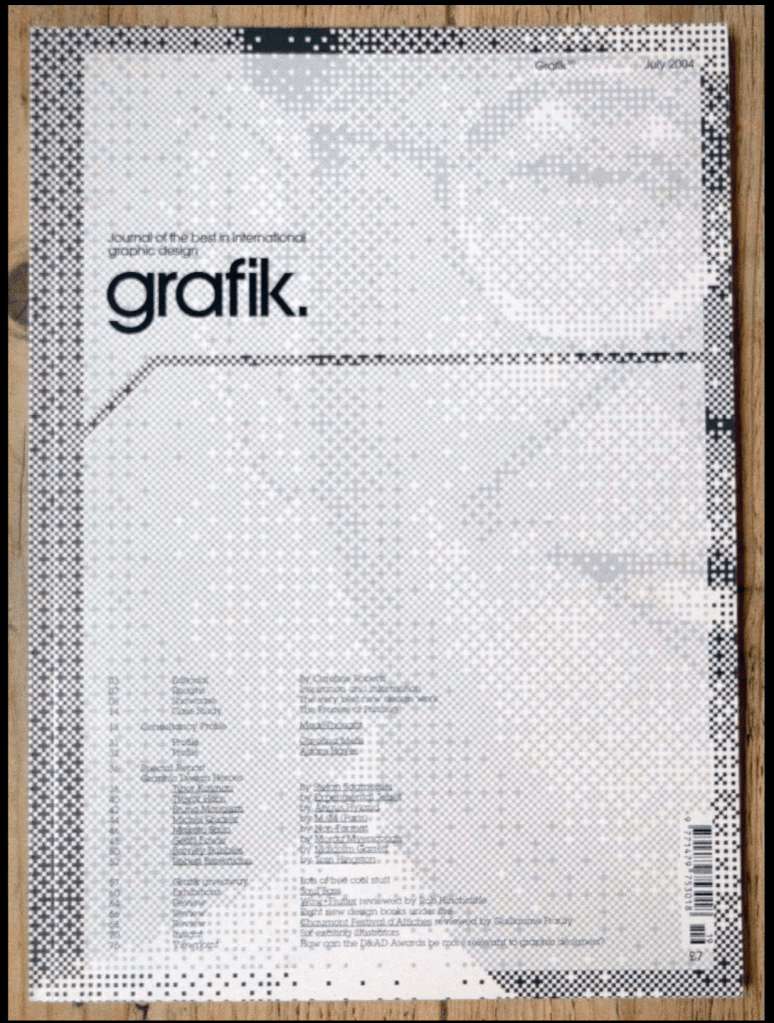

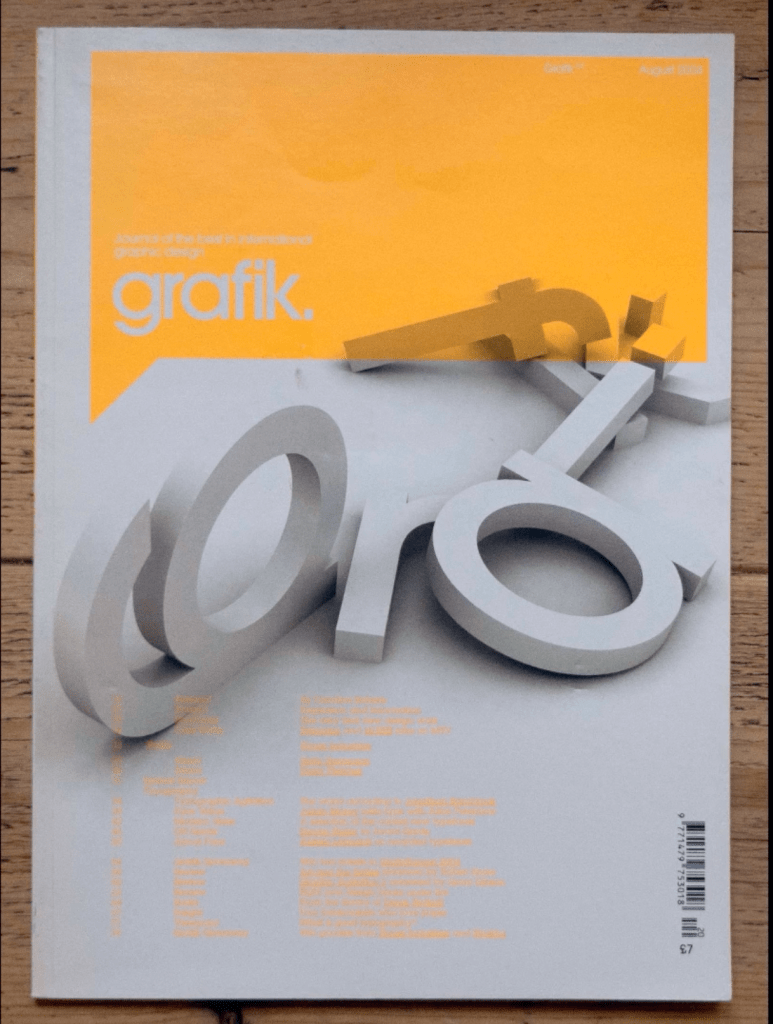

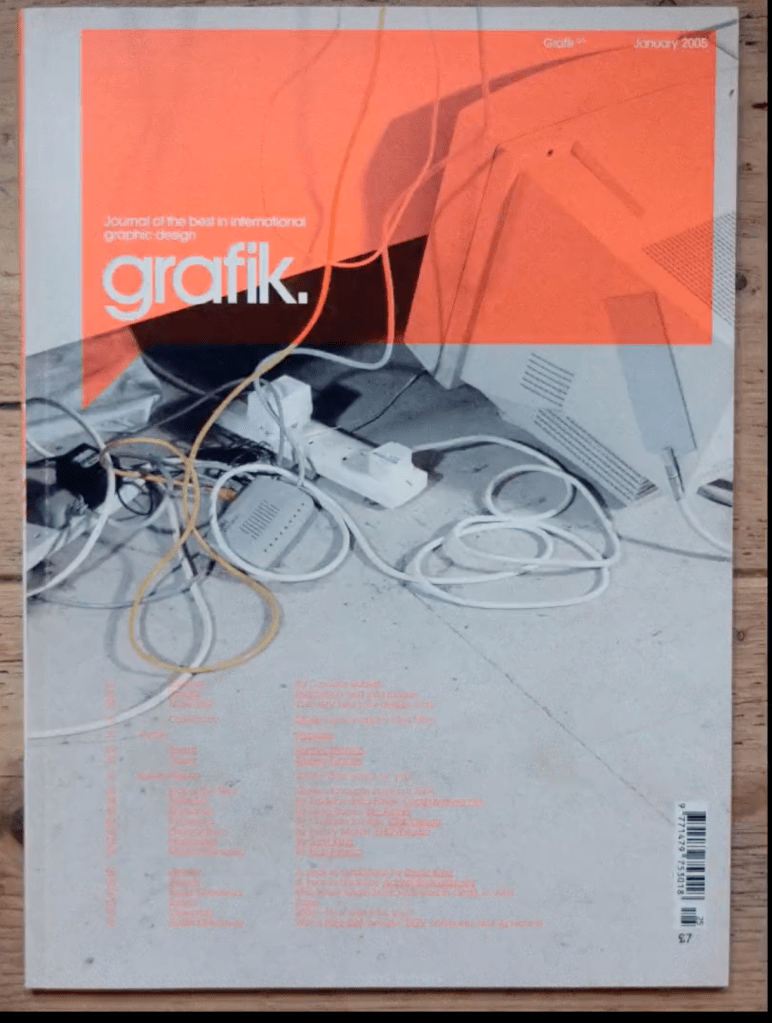

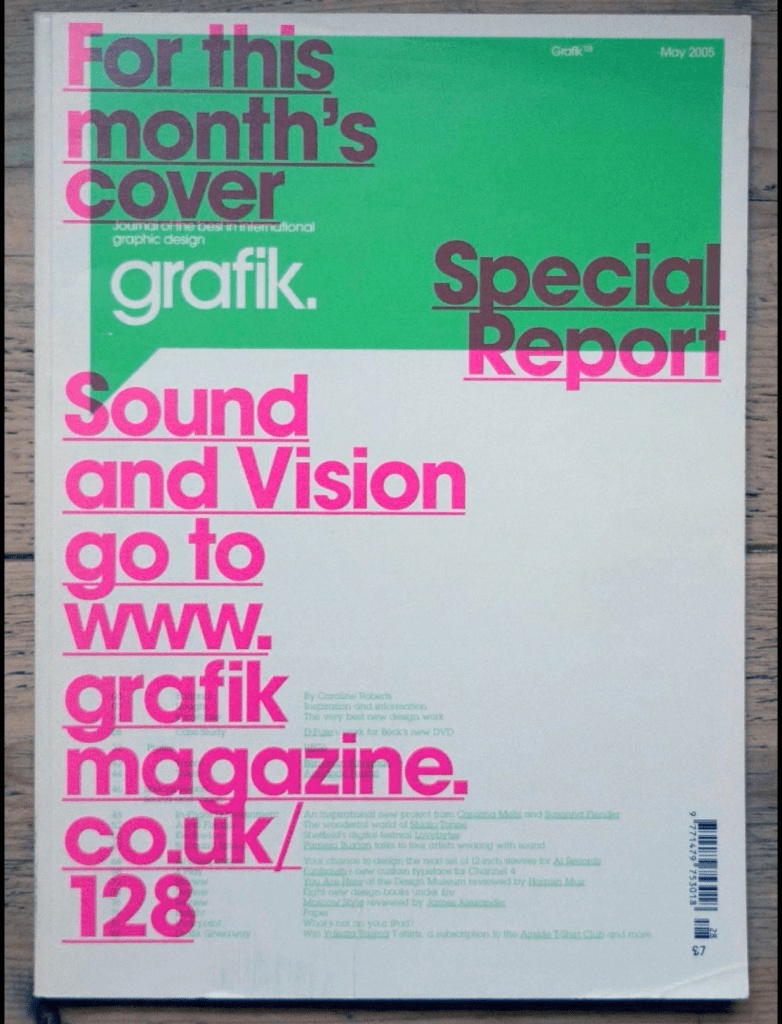

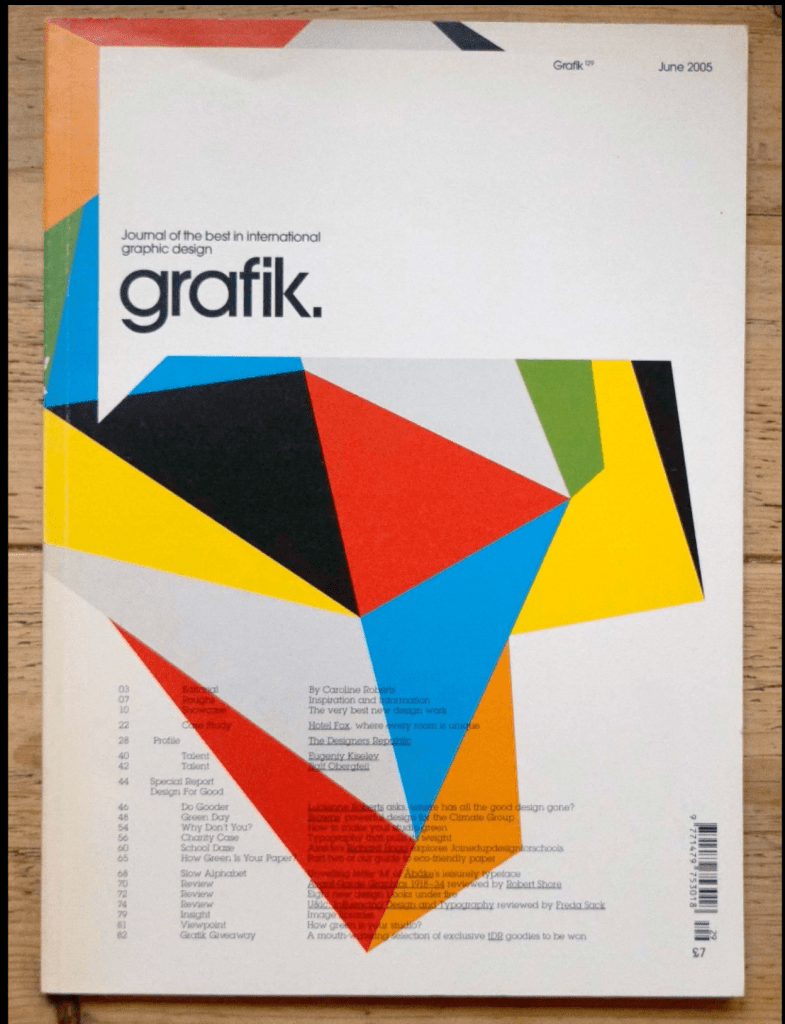

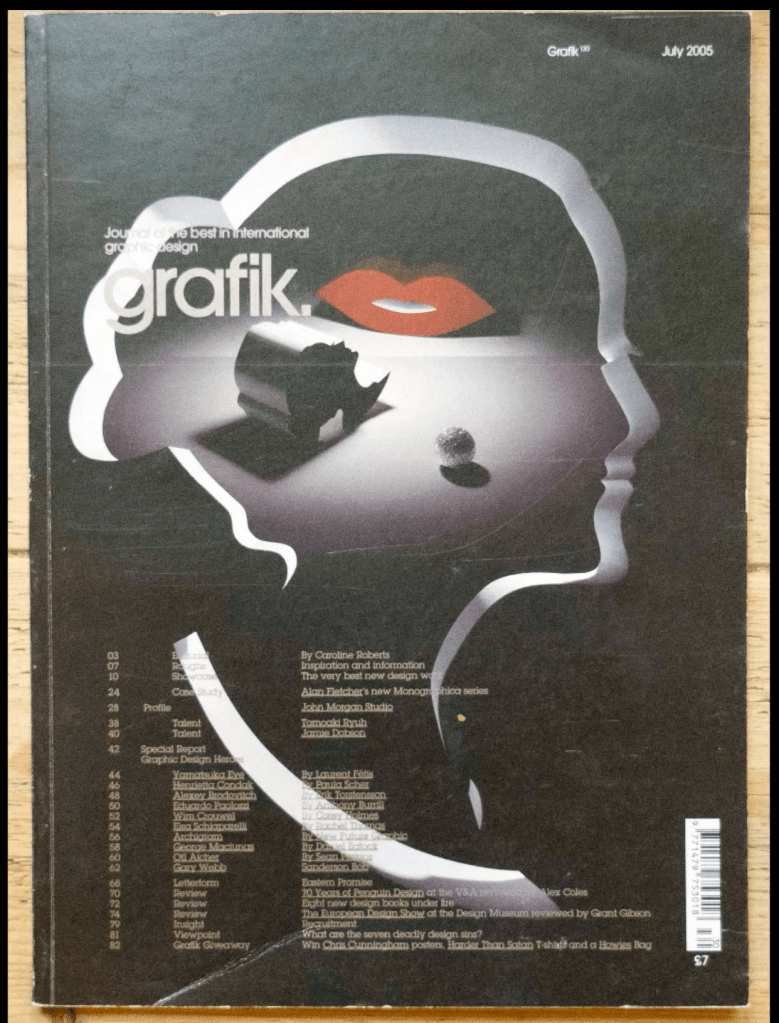

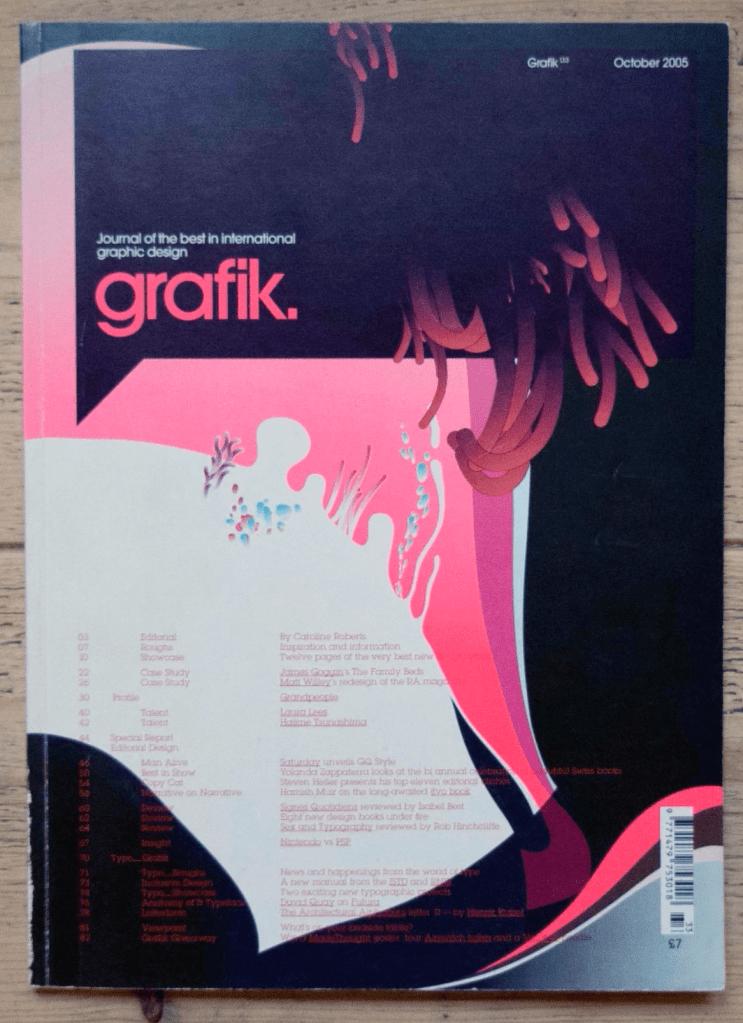

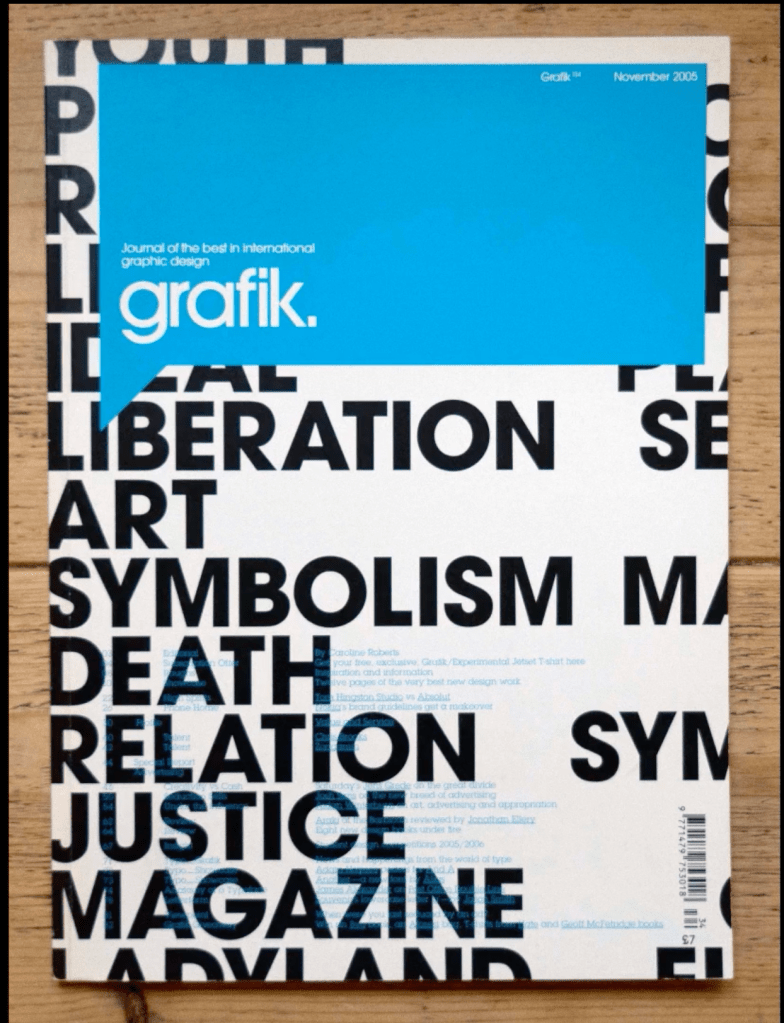

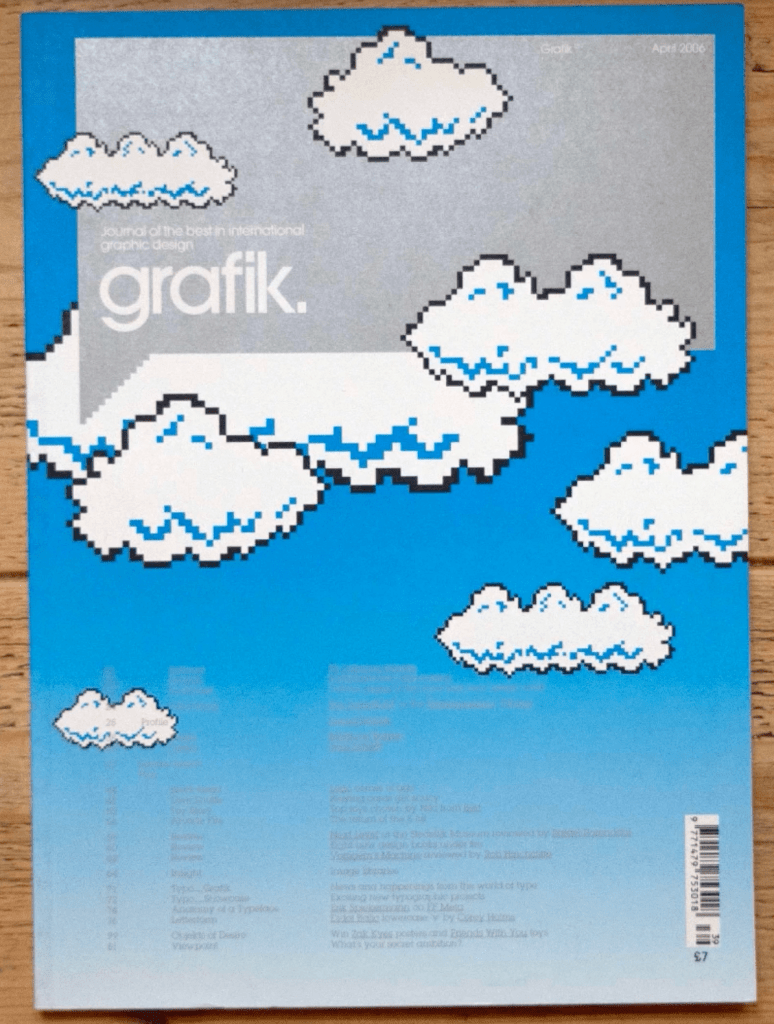

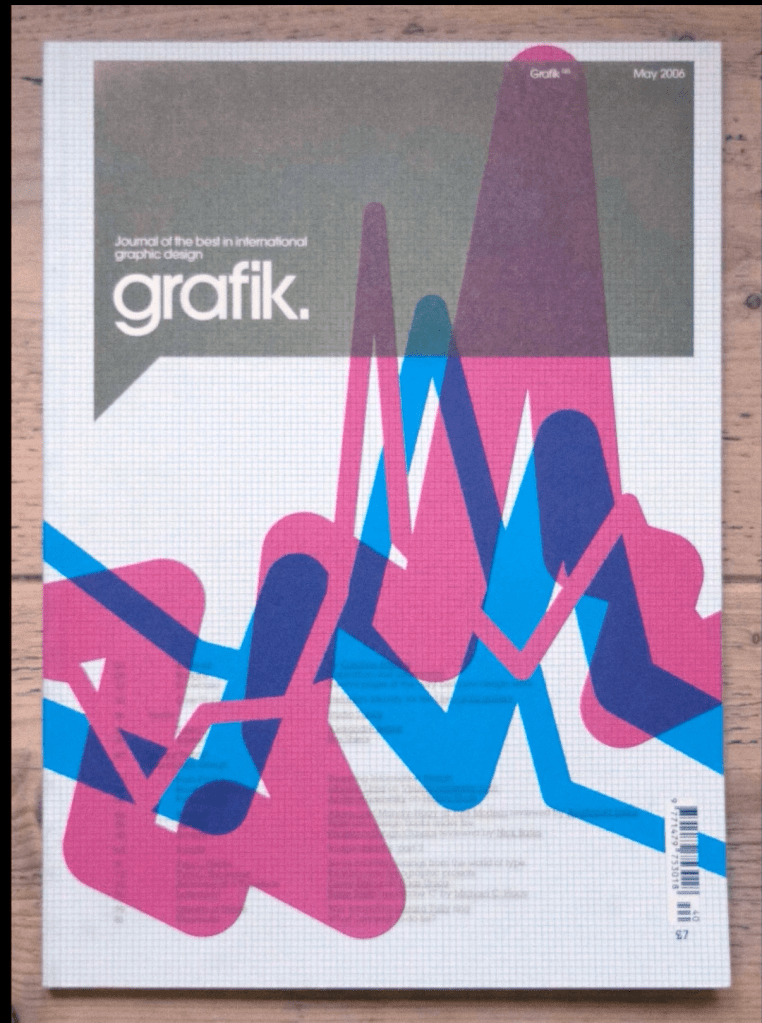

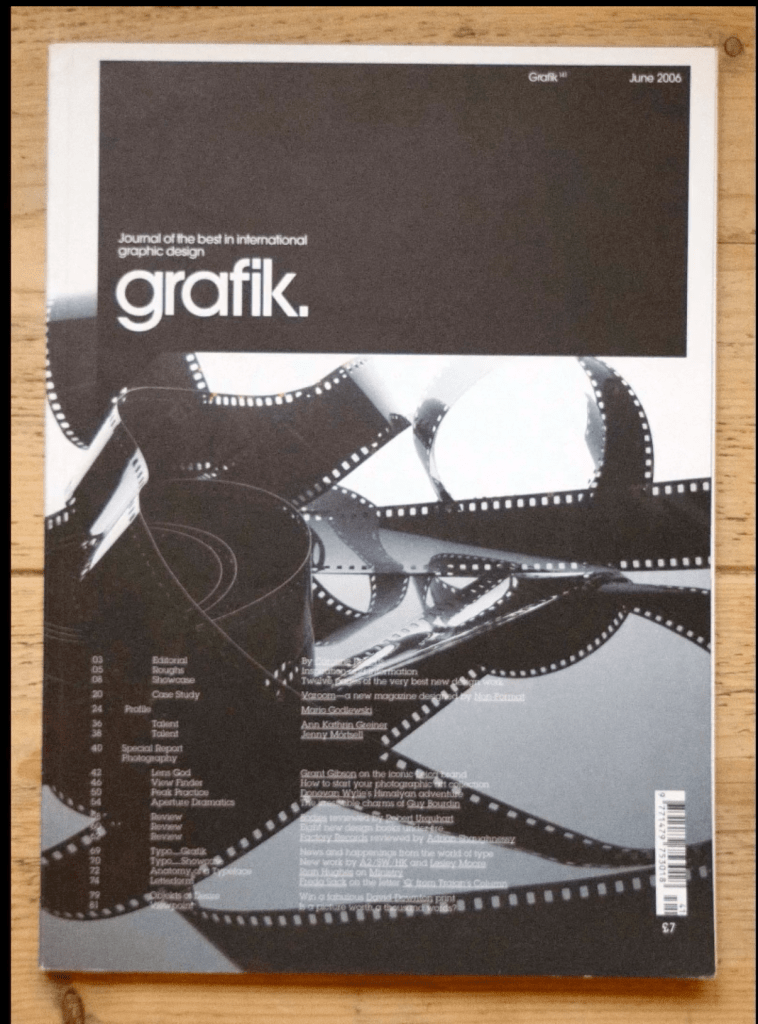

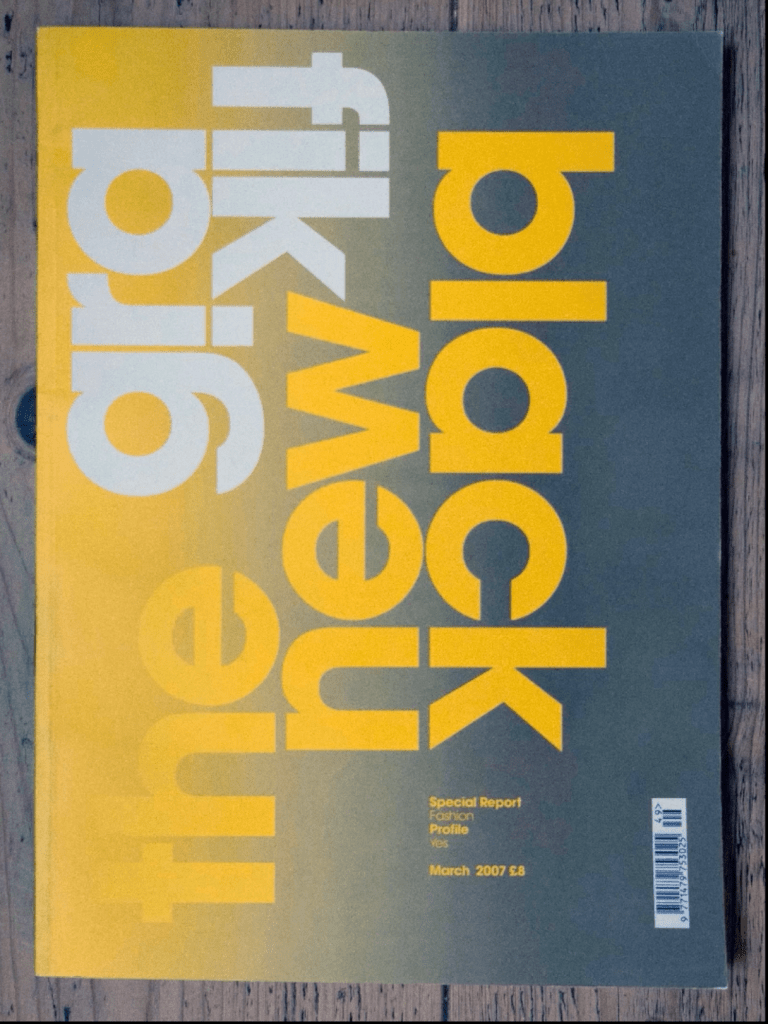

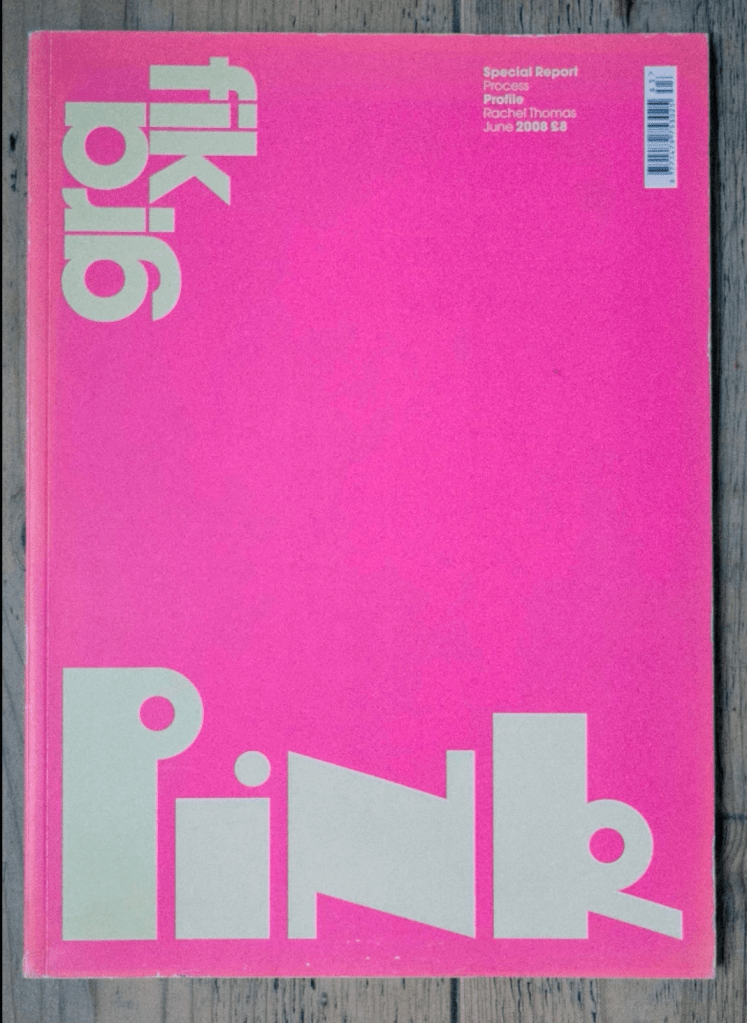

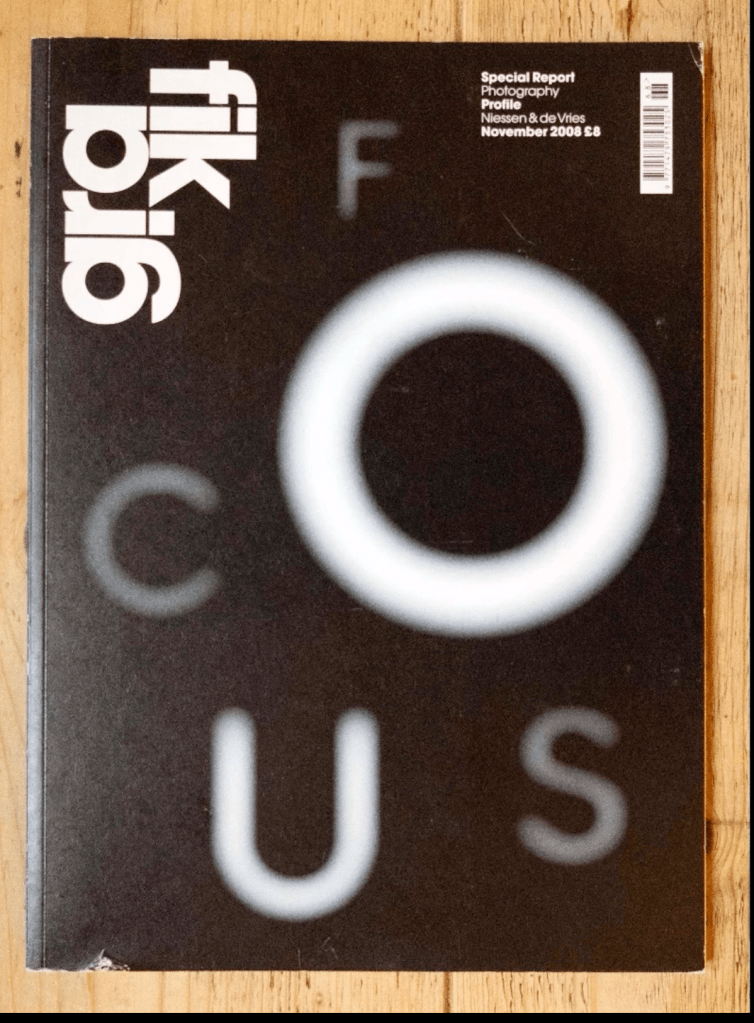

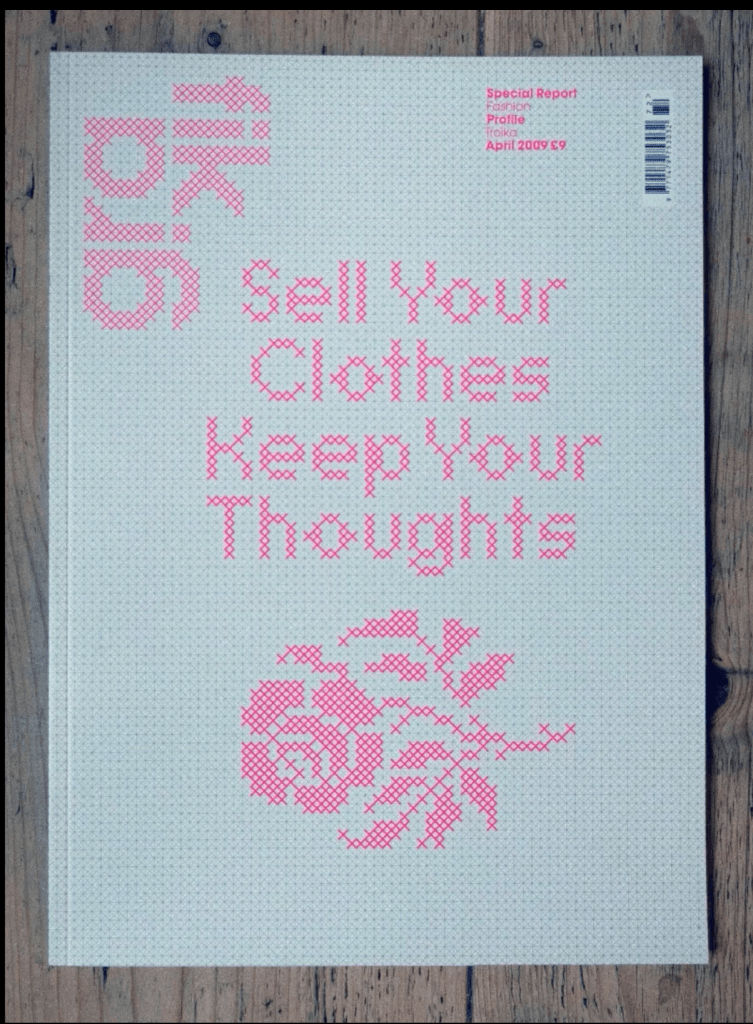

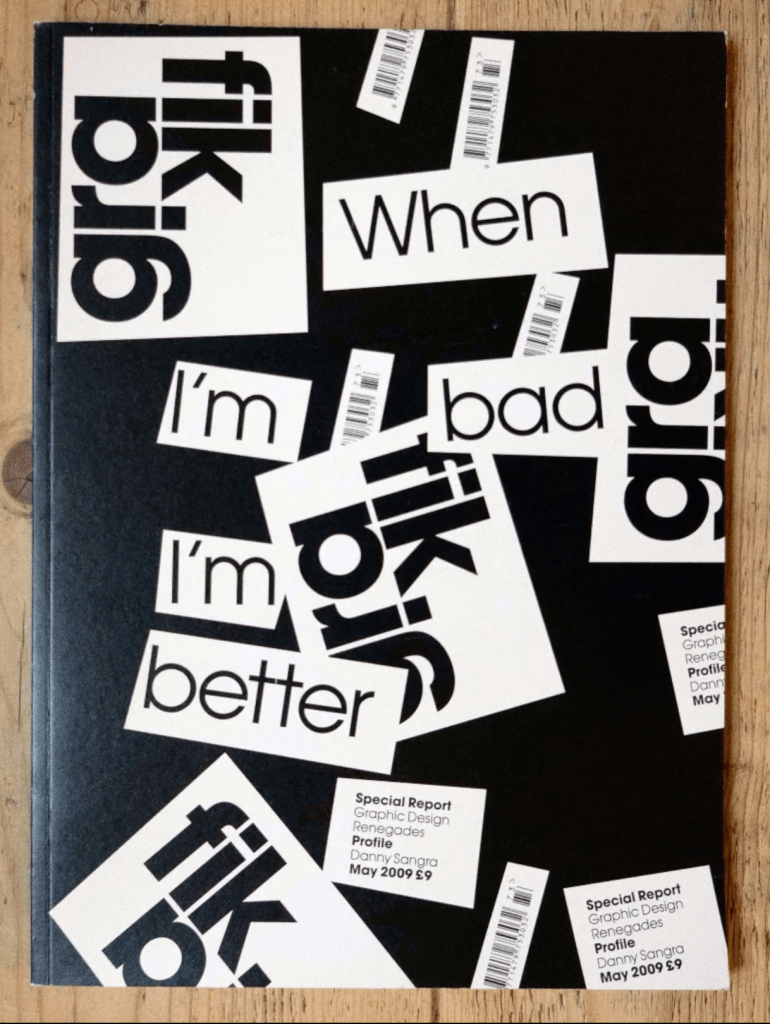

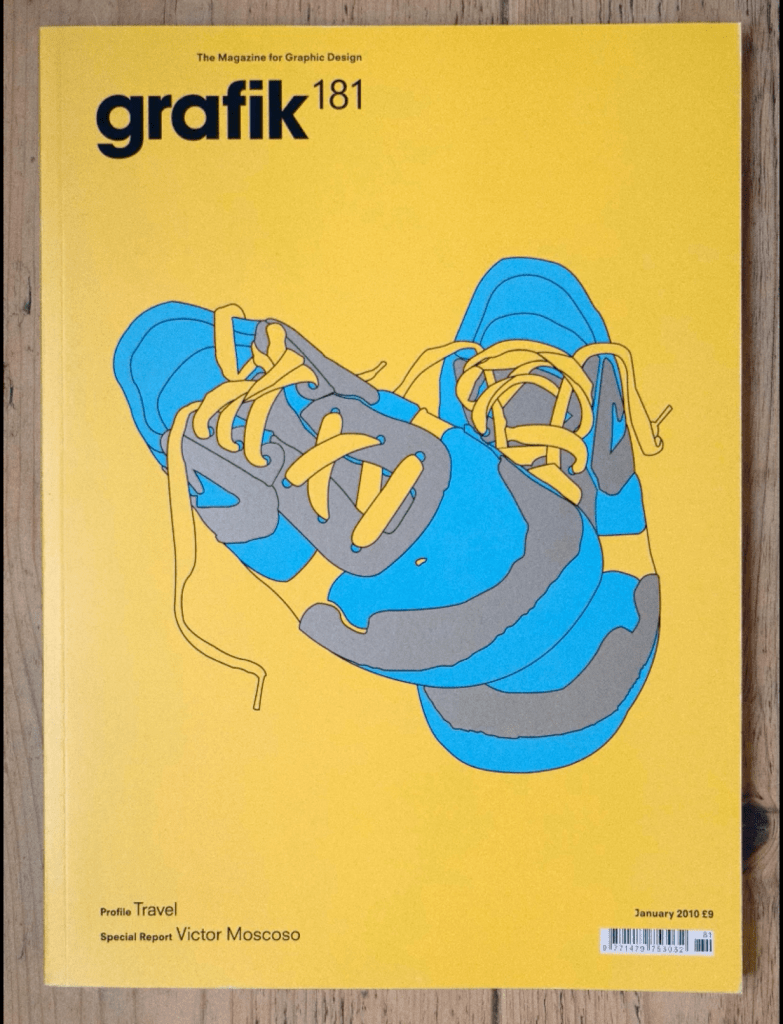

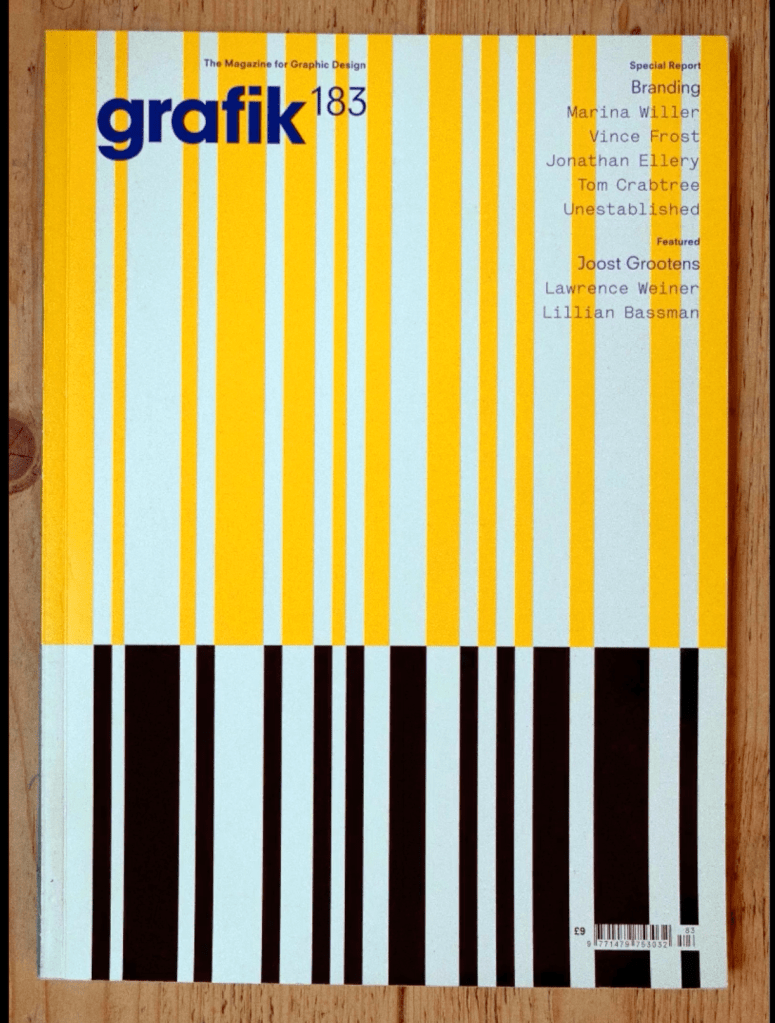

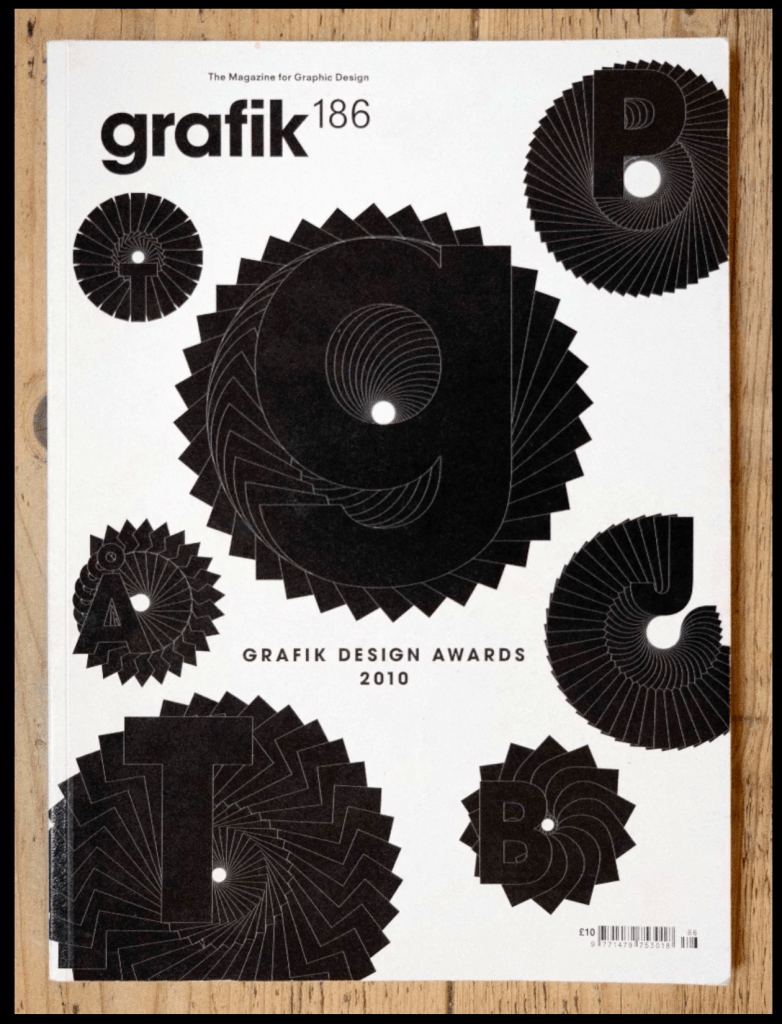

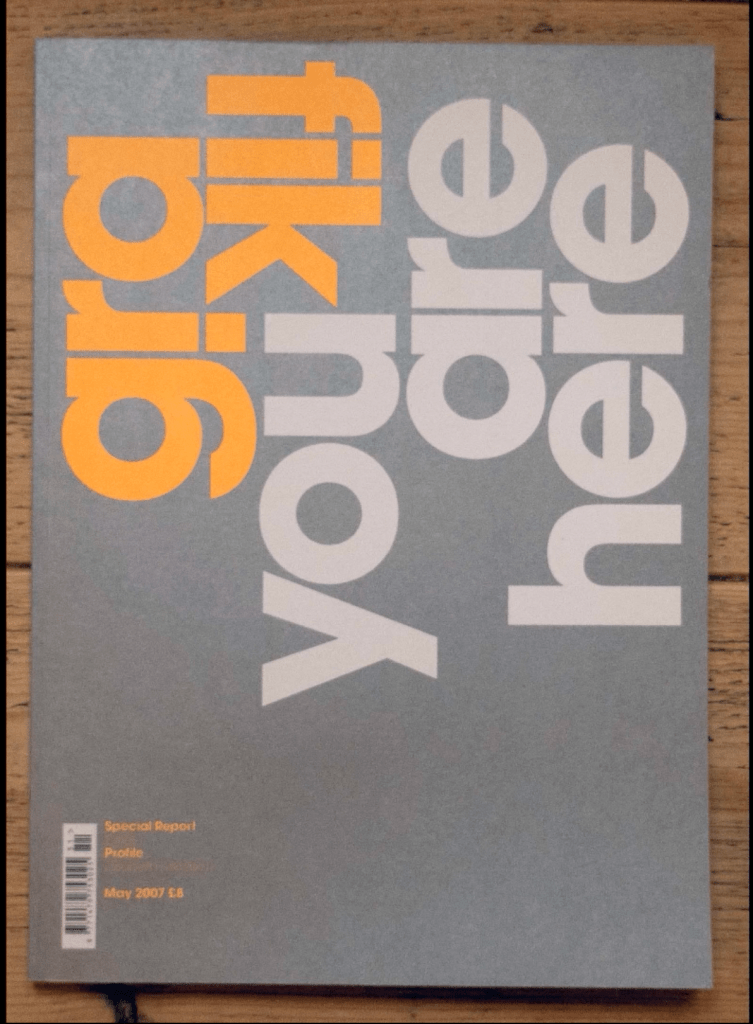

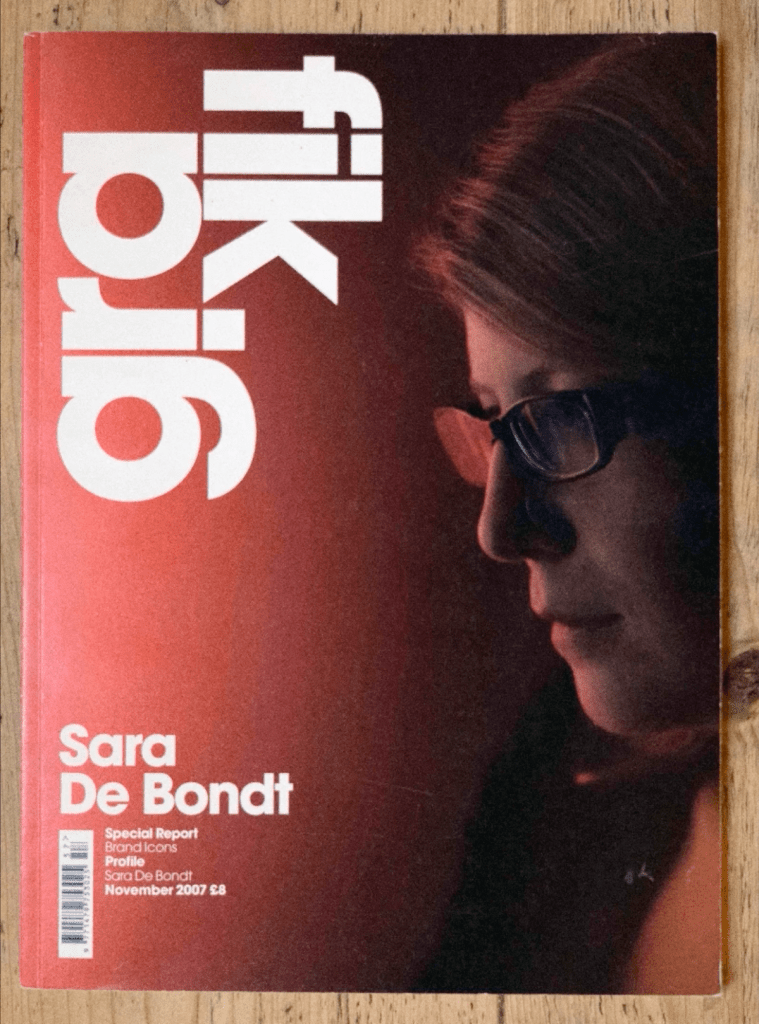

Graphics International was responding to changes that were happening in the world of design, but specifically graphic design at the time. The title wasn’t really reflecting the exciting part of the industry, which was this upsurge in independent design studios; they were doing the interesting work, with people coming out of design schools and the RCA and setting up studios, lots of little independent studios proliferating. They were doing the work that we were really interested in.

Home

“Just to give the students insights about the process of writing, once you’ve selected a subject, how do you structure an article? What’s the process that you go through?

Well I guess it really depends on the context… what kind of publication it’s in or what context it’s being published in, because you might be commissioned to write a certain type of article. It could be that it’s a feature interview, or it could be that it’s an article on a design studio, or something that’s happening in design that’s part of a wider thematic for an issue of a publication.

That immediately sets certain parameters, like how it relates to other content, or word length, or what the audience is like. Think about the contents and the audience for how you’re going to structure it. A long form article is going to be different than say, an interview with a designer. Then the structure from there, within that, I think comes from the content, what your research or your conversations with your subjects, or people you are interviewing about the subjects, that sort of sets the shape of the article in some way

If the students are asked to pick a particular theme of their choosing, and they’re asked to write a 300 words editorial piece, what advice would you give them as a starting point, if this is an unfamiliar process and they are actually being asked to design their article? The visual comes into play, but as a designer, we’re asking these designers to think about words before design. Is there any particular advice you would give to them about starting, structuring, and how to make a start on this?

You need to know your theme well and understand your view to begin with, but that quite often can happen in the process of writing. Drafting is certainly important to my process. You won’t have the final shape of the article on the first draft and sometimes you might get started in a place in the story or idea, that you are evolving in the article, and then find that actually you need to make your point by turning it on its head or putting it back into the middle and writing an introductory lead up to it. But I think having a bit of pace and a kind of rhythm and a point, a crescendo, to come to at the end, is important. And it is the classic beginning, middle and end but you might shift those around. I think certainly, definitely you’ll need to go through a few drafts to create something that has a bit of impact in the way you tell the story.

With your writing, how did you develop your written tone of voice? Do you feel like you’ve got an identity with your writing and a tone of voice? Did you craft that?

I think it definitely evolves through doing lots of writing and I would probably look back on things that I wrote early on in my career and think oh goodness, you probably use too many words…

Could you please tell us about that decision, about pulling it from print into online?

People spending less on printed magazines. Digital publishing did affect the whole industry irrevocably. Part of that was the print and paper costs going up, people’s reading habits changing. Another knock on effect of that was things like Borders closing. When Borders bookshop closed, that affected us hugely because it was one of our biggest retailers.

Advertising revenue just went steadily down because advertisers in our industry stopped advertising in print. Yeah, lots of things counted against us that made it really difficult to keep going.

So what were the creative challenges you faced when you were creating content for an online magazine? That must be a very different animal?

It took us about a year to actually figure out how we were going to do it and plan it, because we wanted to keep certain elements of the magazine. We wanted to keep quite a lot of the original print magazine alive and the certain types of article that we had in the print magazine, but also, we knew we had to adapt a bit as well for the platform and the readership.

The length, I guess the length of articles changed. The pace and how people consume them? Also, you have this archive, which was really different to, unless you’d bought every issue of the physical publication, actually go back in and search and find. I think that it’s a totally different animal.

Yeah, well I mean we came up with this short, medium and long. Short articles, medium articles and long articles. Then we had certain themes and approaches that we’d do under short, medium and long. We had this whole set of articles that were based on the Letterform article that we had in the magazine, which was a short, double page spread, like 300 words and a letter form.

You’ve written a book, a fantastic book called So You Want to Publish a Magazine, which is published by Laurence King? Can you tell us a bit about it?

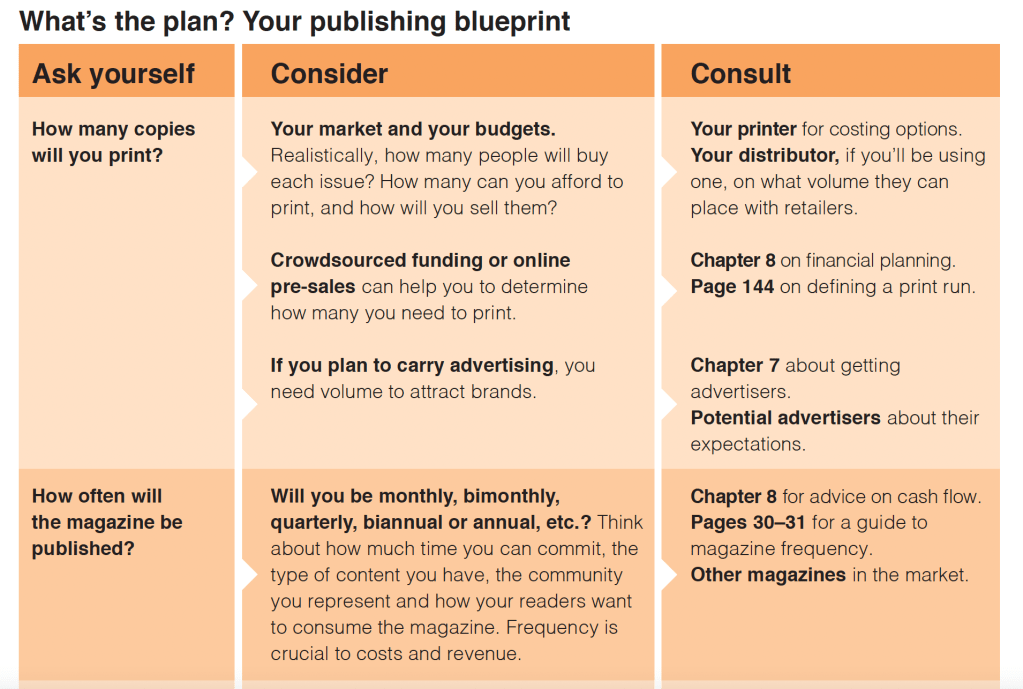

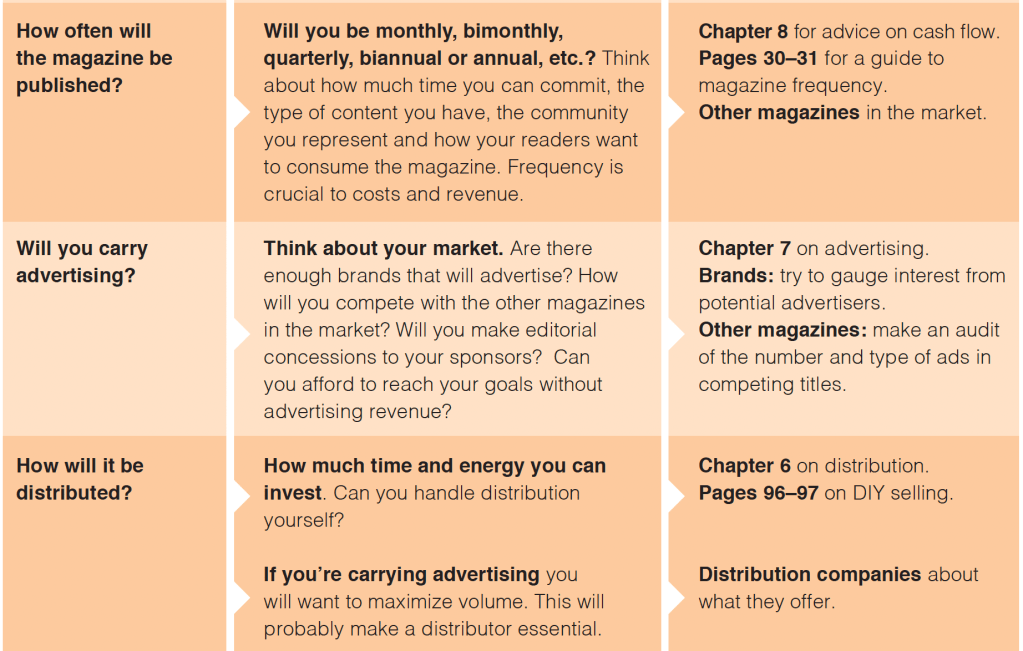

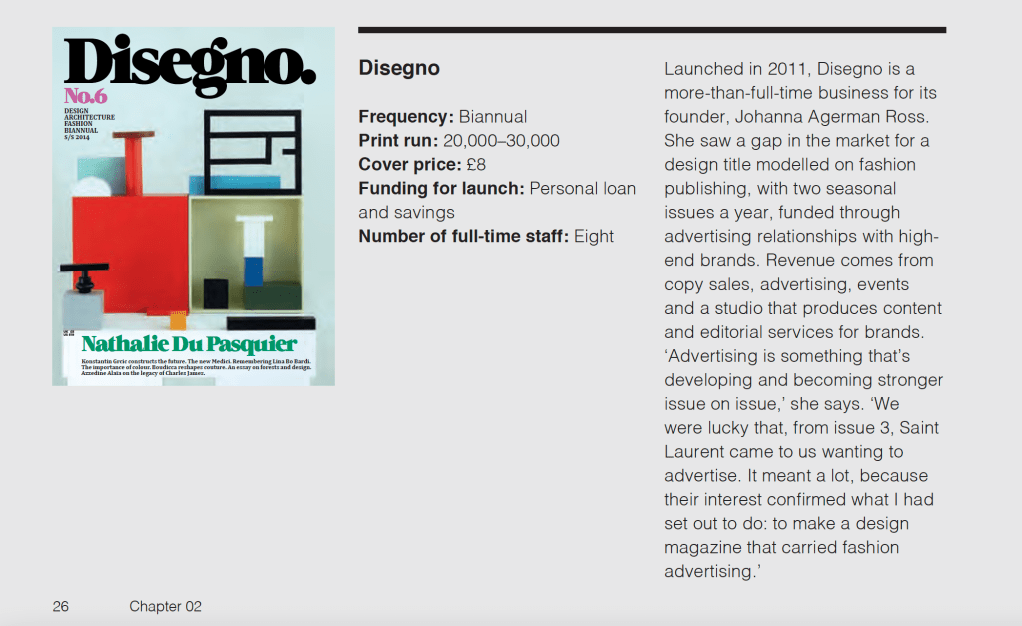

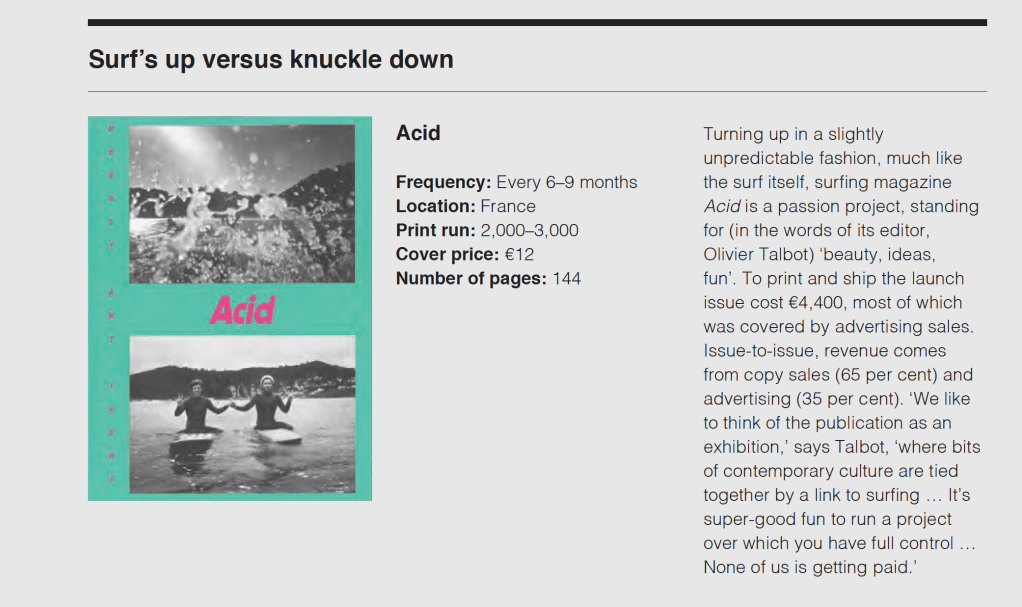

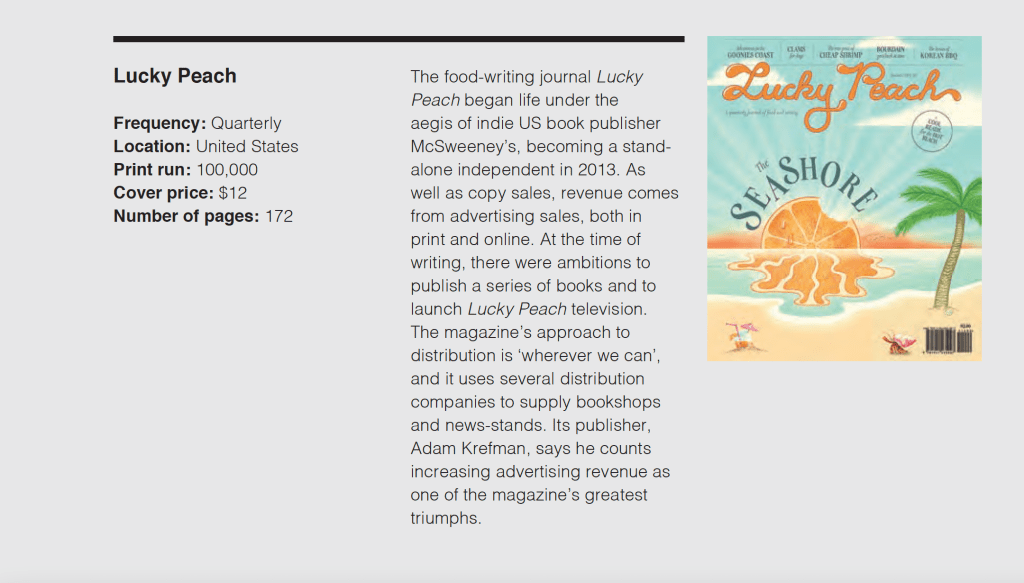

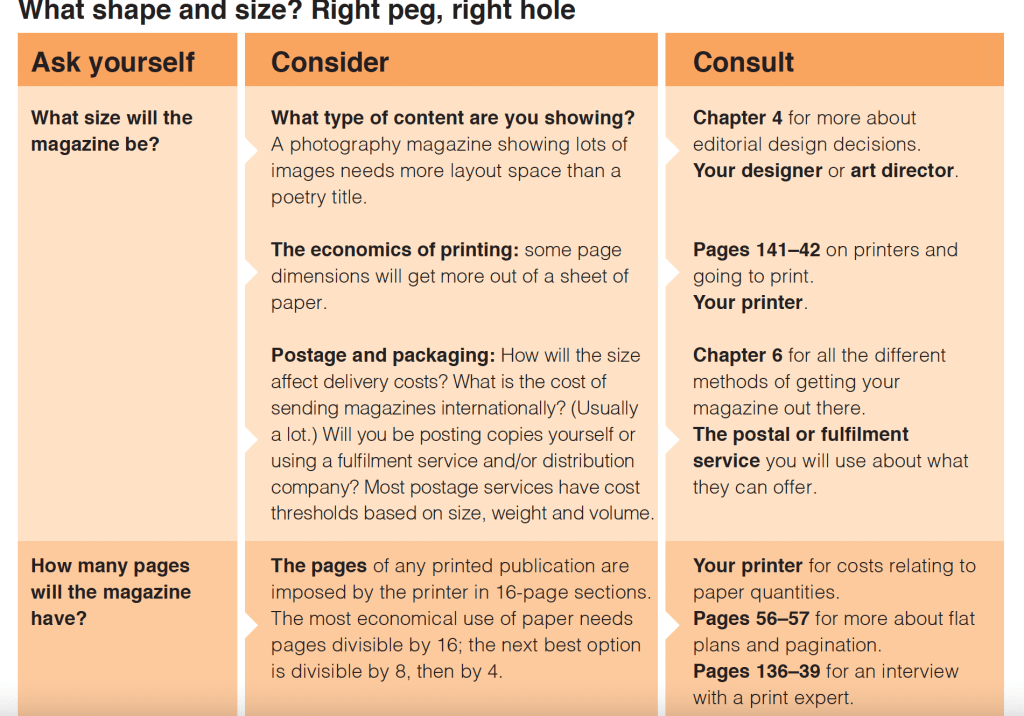

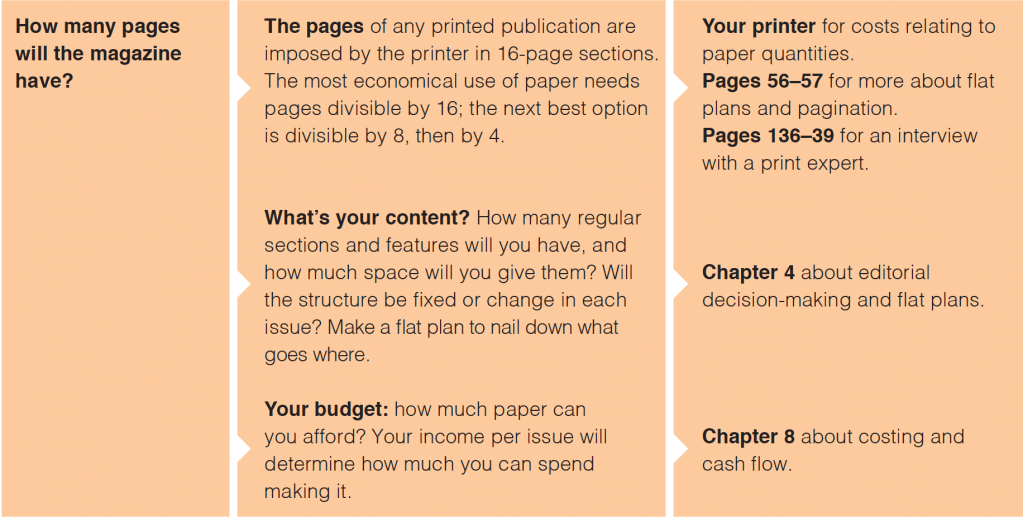

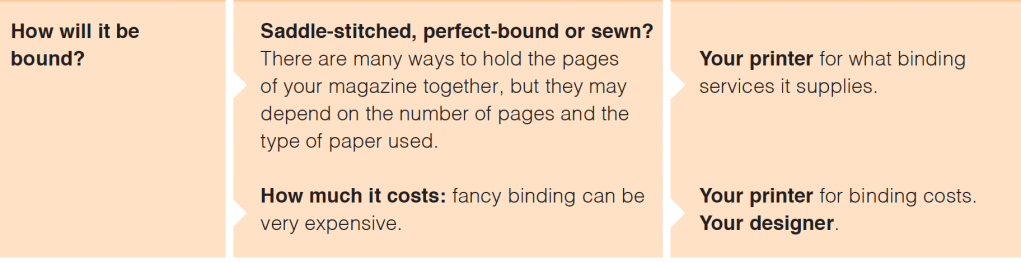

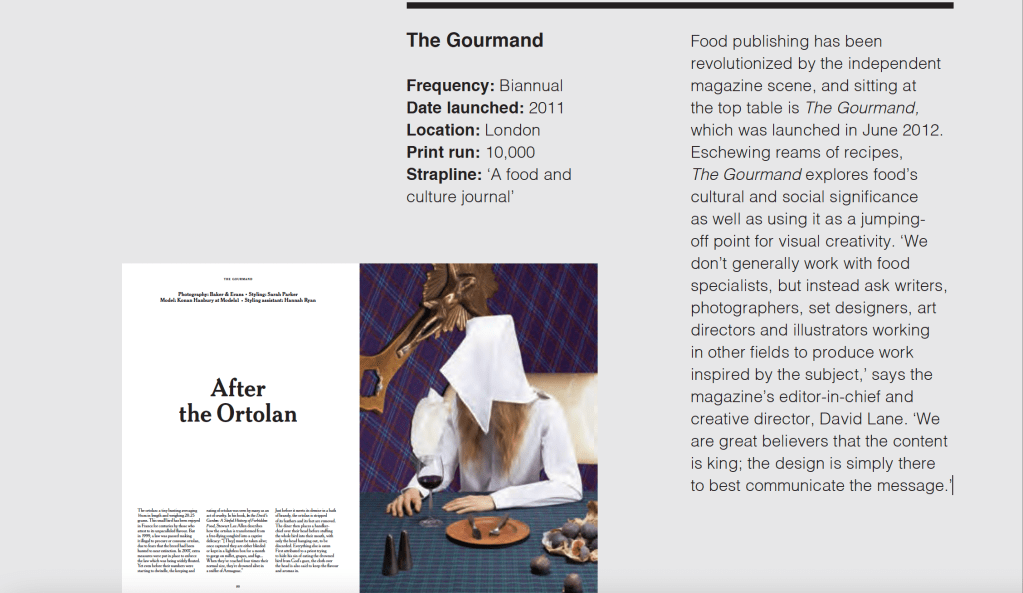

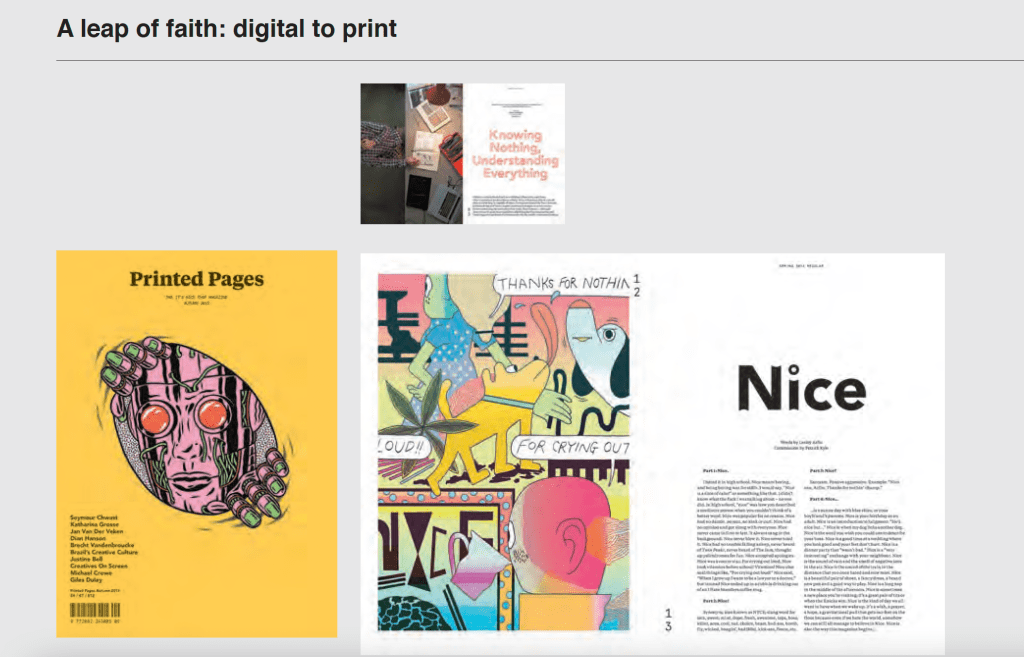

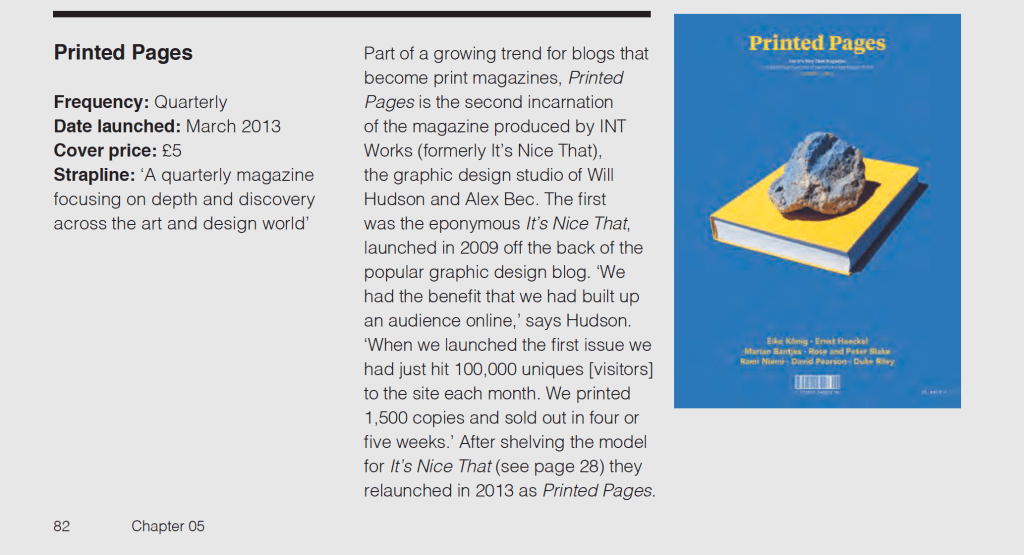

Yes, it’s sort of a survey of the independent magazine publishing landscape, in that I wanted the book to bring together all of the knowledge and knowhow of people independently publishing magazines. In the gamut, from really small zine-like magazines to the opposite end of magazines, like The Gentlewoman, where it is an independent magazine but is quoting 100,000 copies and has huge advertising revenues. Looking at the gamut of that, bringing all viewpoints and the knowledge and experience together to help all people start their own publishing projects.

Books have a longer shelf life than magazines and especially online content. Did you have to adapt your writing process when creating content for your book, back from your experience of having worked online?

Not hugely, but I did have a bit of angst for a while about how long the gap was between me creating the content and the book hitting the shelf, especially as it was about magazines. I was worried about it not being current enough when it was on the shelves, but in fact the publisher talked me down from that angst. He was like, a book is a book, it’s not a moment in time.

Looking at how publishing’s changed over the last decade, could you set out some of the main changes that you’ve seen in your career and also maybe move on to talk about ideas for the future of publishing? Quite big question.

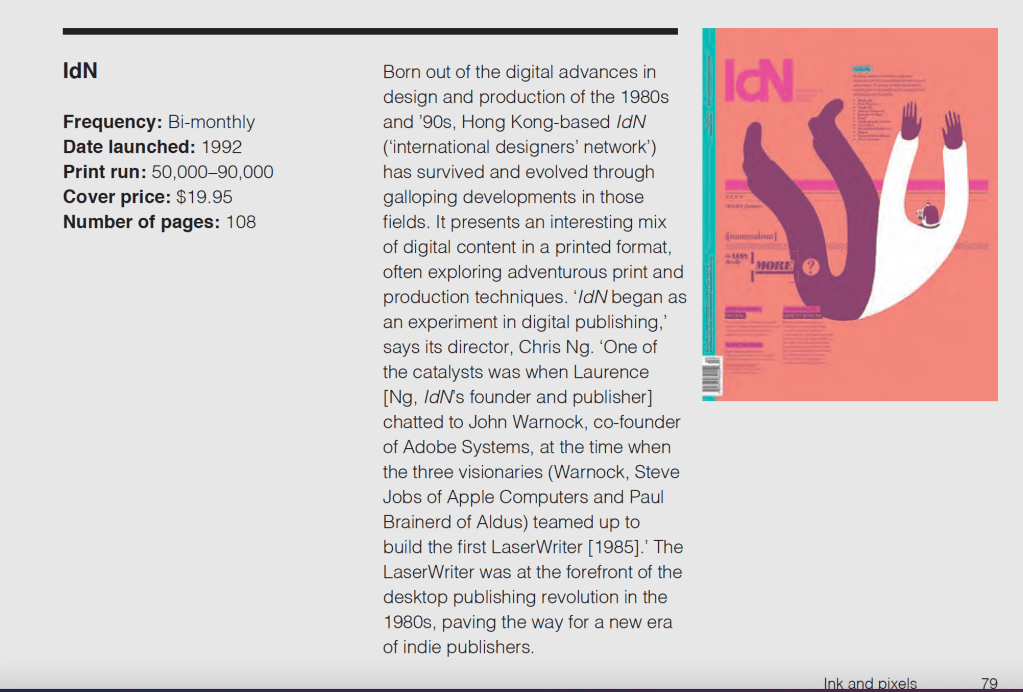

Well, I think the biggest thing definitely that’s happened in magazines is the rise of independent publishing. Just the way that’s reinvented magazine formats and approaches, especially with niche titles. All those things, those subject areas, that magazines have been about for ages – like food magazines and current affairs magazines – have been reinvented in so many really interesting ways by independent publishers.

And you know, the downfall, in the way, of a lot of the established publishing or print publishing worlds has created spaces for people to be really inventive. Audiences have changed in their expectations so how many people actually buy a weekend newspaper now compared with 10 years ago? People’s buying habits for magazines have got a bit more book like. You might buy three or four fairly expensive magazines a year.

1. Lewis, A., (2016) So You Want to Publish a MagazineLinks to an external site.. London: Laurence King

“In our dreams, the magazine we love is created in a fantastical space. The reality is often a messy office at the top of too many flights of stairs in a cheap part of town, or a space cleared on someone’s kitchen table. For the many independent publishers of the world, however, that is not a turn-off, but rather part of the buzz. Out of all that chaos and sweat comes something beautiful that will sit proudly on the bookshop shelf or make its way through hundreds or thousands of letterboxes around the world.

You will probably change your mind a hundred times along the way, and keep making mistakes, but the beauty of magazines is that there is always another issue in which you can fix what’s not working and try something new.

Very few independent magazines are just a magazine, and of those that are, fewer still are run as stand-alone businesses or full-time, paid occupations for the makers. For most people who publish a magazine, that is just one part of what they do; they might also have a day job to pay the bills, or run a related business such as a shop or design studio. Nevertheless, taking on the massive workload of a magazine is driven by a need or a passion; it could be an individual’s obsession with a subject or hobby, such as poetry or cycling, or the magazine might be part of a bigger business model, providing a showcase for a particular product or service and attracting new clients.

Monocle magazine is often cited as a pioneering example of a successful independent publishing model. In September 2014 it was valued at $15 million after it sold a 5 per cent share to the publishing arm of the Japanese news agency Nikkei. The magazine is just part of a brand that also includes a shop, a radio station and cafes, all run in parallel with editor-in-chief Tyler Brûlé’s successful high-end branding agency, Winkreative

So ask yourself what your goals are. How ambitious are you? Is your magazine going to be your main occupation – a profitable venture – or a part-time creative outlet?

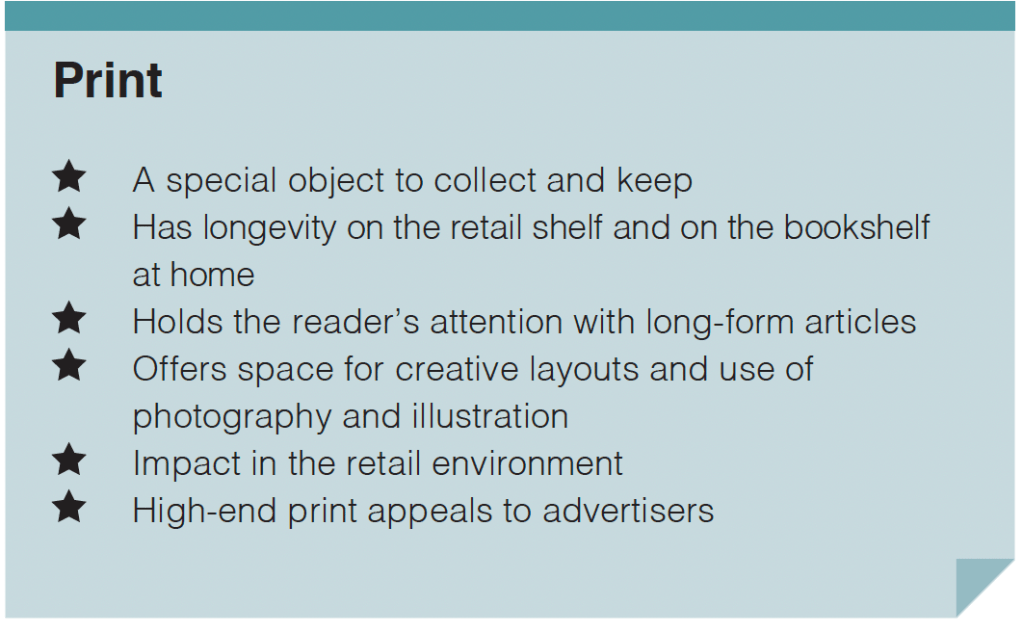

“What is the function of print today, and can I create value in this medium?”

It has never been easier to make and publish a magazine. Desktop technology puts design and print production at the fingertips of anyone who is willing to learn the basics; commercial printers in a squeezed market are increasingly happy to take on small run jobs to reach new customers; and independent shops enthusiastically take on small titles to create a unique offering for shoppers and justify their existence in competition with high-street chains and online retailers.

But this is also an extremely competitive world. If you’re trying to attract readers in bookshops and newsagents, yours will be one of many new titles every month, up against established favourites.

The idea that print is dead comes up again and again,’ says Matt Willey, creative director of Port and the New York Times Magazine. ‘Print isn’t dead. And right now is a really, really interesting moment. But you have to justify your presence in print, which is a good thing.’

“What is so special and unique about my idea that I’m killing trees for it?”

Today, anyone publishing in print has a duty to think responsibly about the resources they are using.

“Print and digital are equally important for the business.”

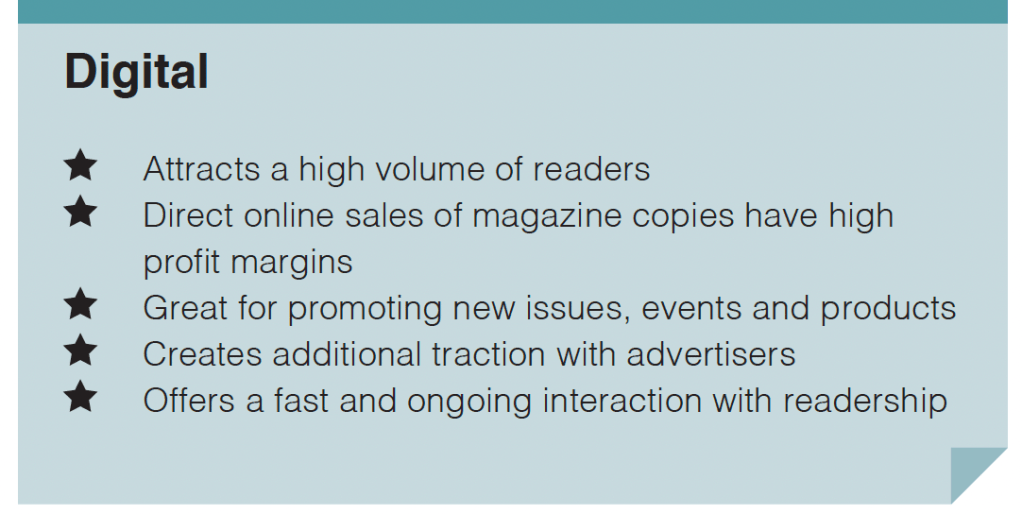

There are many examples of magazines that began life as blogs before becoming printed objects. Publishing online can build a loyal readership, some of whom can be translated into customers of a printed publication.

“Do I have a unique idea? Is there an audience for it?”

You may care passionately about your subject, but you must make something that other people will regard with equal fervour. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Once you’ve established that there is an audience for your magazine, you must let enough people know about it, inspire them to buy it, and keep delivering content and design that make them crave the next instalment.

“Are you bringing something new to your project?”

The world of independent publishing is tough enough without trying to publish a magazine that already exists. Your idea and your voice must be original.

However you approach making a magazine, you need to be seriously dedicated. As everyone in independent publishing will tell you, it’s extremely hard work and will takeover your life; when the fun jobs of putting together the editorial and design are over, you’ll be up until the small hours ordering bar codes, collating orders for your fulfilment house, responding to readers’ cries of ‘Where’s my copy?’ and working out the print schedule for the next issue.

“Are you prepared for all the unglamorous jobs – marketing, distribution, finances, taxes, stuffing hundreds of envelopes?”

Is your Dazed Digital audience different from that of the print magazine? It’s bigger and the gender is less female. Print is probably 80 per cent female, and online is more like 65 per cent. How do you make people stay on your website and keep coming back? It’s the power of the story and how you tell it. We have different frequencies of story-telling; not everything has to be short to win on the web. A lot of the metrics are changing, and what we look at is engagement, not hits. We look at time on site and the interactivity we get, like commenting, which means readers are emotionally engaged with a story and are likely to ‘share’ or ‘like’ it. Engagement is much more important to us than just the top-line figure of how many people landed on a page.

So we’re moving from what we call the ‘click web’ to the ‘attention web’. I’m very interested in that from a story-teller’s perspective – the change in how we measure behaviour and quantify it.

I want to understand people’s total attention, not just where they’re clicking.We’re in the early days. It’s going to evolve; there’s much more beauty to emerge from what’s happening online. Print has been around for a very, very long time. It’s only really in the independent sector that anything interesting is happening in print. You really, really have to push it now to do anything that’s interesting or modern-feeling, because most of the best work in print was done in the 1960s and ’70s and most of what happens now is a copy of that. I see very little in print now that’s new, and when I do see it, it’s in the independent press because that’s where people are taking the time and passion and putting the work into doing it. But on the web I see it every day.

Finally, be more than a magazine

Print magazines are no longer the hungry reader’s only connection to ideas, trends and information, as they were in the pre-Internet age. They have begun to settle into a slower pace, closer to that of books, balancing book-like production values with the time and change-marking qualities of periodical publishing.

David Lane. ‘We are great believers that the content is king; the design is simply there to best communicate the message.’

The boom in the independent magazine world has proved that there is an appetite for well-made printed publications. A lot has been said about the Internet being a disaster for publishing, and indeed it has made fast-paced news in print increasingly redundant, but for independent magazines it is an important ally. Indies tend to publish between one and four times a year, so the speed of digital publishing is not a threat. Indie titles make the most of what it means to be in print – long-form journalism, wonderful layouts, good design and high-quality production and papers.

Social media

Social media is a powerful tool for independent publishers. Even with no marketing budget, an independent title can promote sales with a strong social-media base. Social media is your biggest friend when it comes to building up an online community, and that is important if you are trying to drive sales through your website and let people know when your latest issue is in the shops.

‘We would never put anything on social media that we wouldn’t put in the magazine,’ says Rosa Park of Cereal. ‘Whether you’re reading our magazine, reading a blog post, looking at our Instagram or flicking through Tumblr, any of those channels on their own should give you a very clear indication of who we are and what we do. That’s our approach to social media, rather than “Hey, here’s a snap of our office today.”’

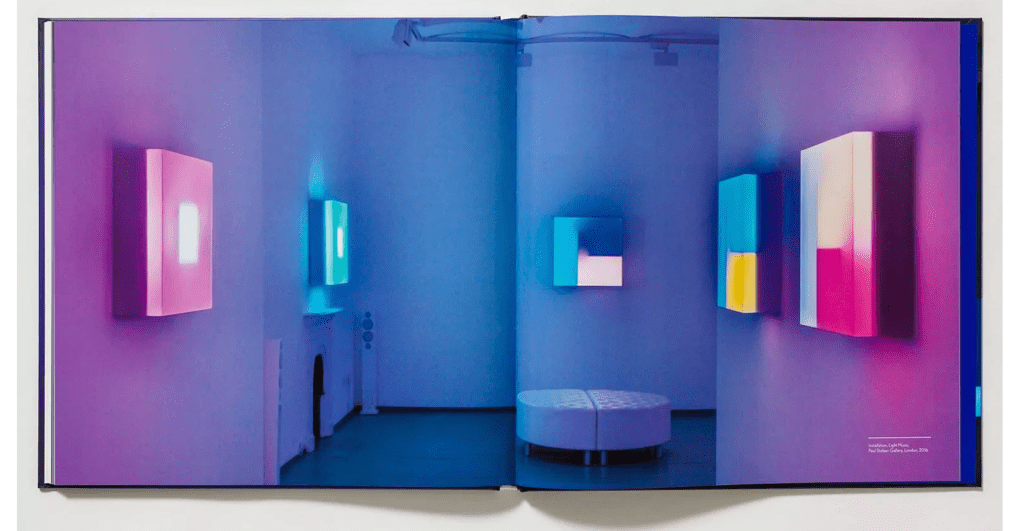

https://www.wallpaper.com/art/brian-eno-light-music-book

Colour theory: Brian Eno reflects on light and listening in his new tome

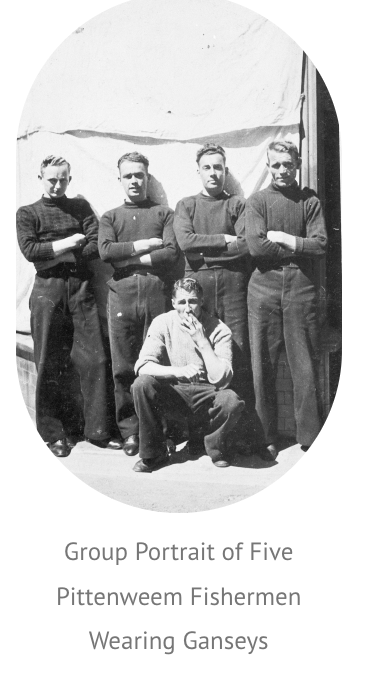

From when they started out in the industry as young men, most Scottish fishermen (between the late 19th and early 20th century) would have owned at least one gansey, usually dark blue (but sometimes grey, cream or even red) tightly knitted sweaters, created for them by a family member. Made of strong and water-resistant wool, ganseys were designed to be practical and comfortable, and came to play a vital role in Scotland’s fishing communities. Over time, they became fisherfolk’s distinctive knitted workwear, often worn as a source of pride.

https://the-book-design.tumblr.com/

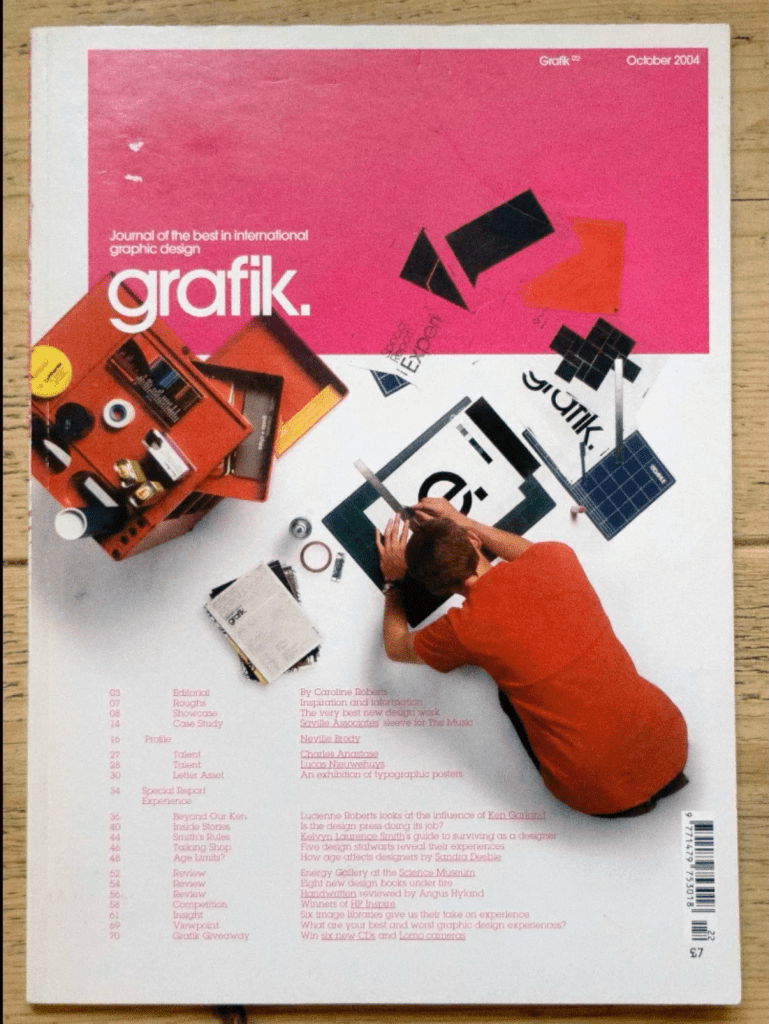

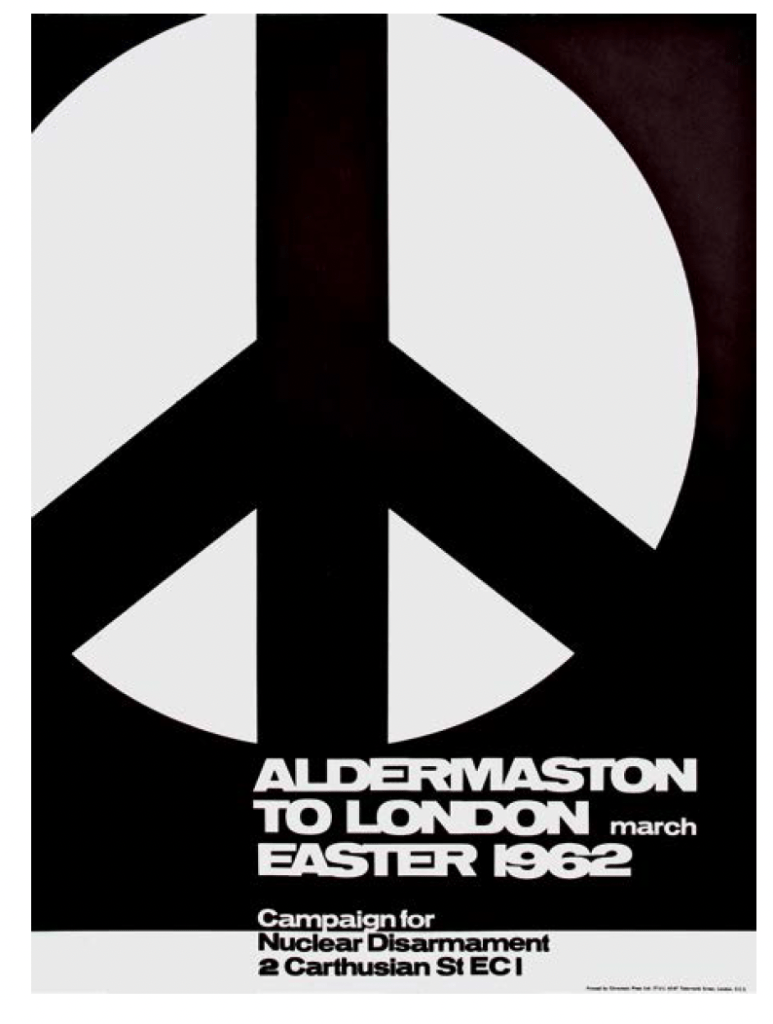

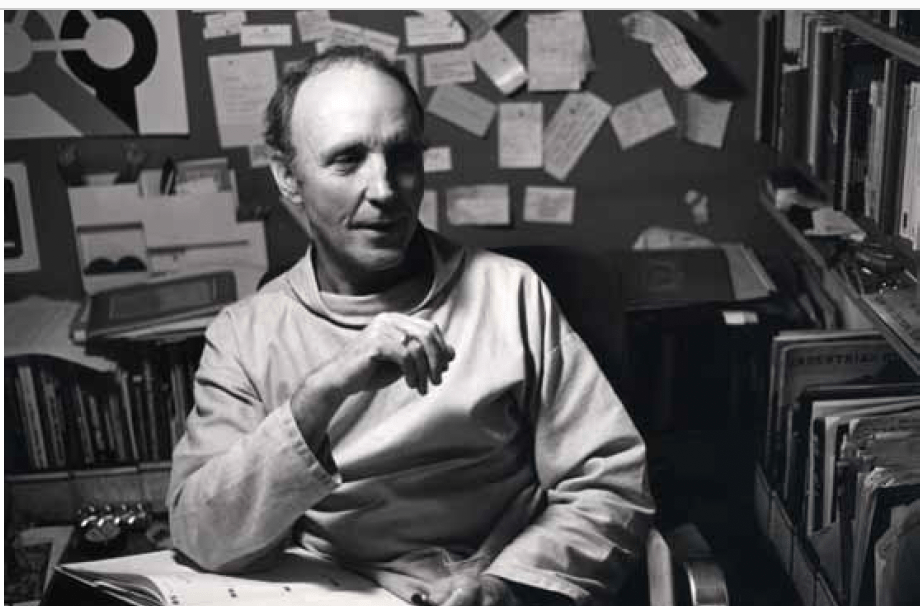

…Ken Garland laid out his design philosophy in 1960 in an essay entitled ‘Structure and Substance’24 – after which this book is named. Reading his concise text (devoid of the vernacularisms – ‘let’s face it, chums’ – that cloud some of his later writings), it is possible to see how his practice was forged from a sophisticated knowledge of 20th century visual art and design. He references the Arts and Crafts movement, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Dadaism, Constructivism and 1920s avantgarde cinema, and draws the conclusion that it was a ‘synthesis of these ideas, with their oppositions as well as their common factors’ that created modern graphic design as it appeared in the late-1950s and early-1960s. In 1960, at the request of the Council of Industrial Design, Garland went to Switzerland to survey Swiss graphic design and printing. There he saw the work of, amongst others, Max Bill, Richard P Lohse and Max Huber. The mastery of structure deployed by the leading Swiss designers impressed him: ‘Their work retained the frugal appearance of the New Typography of the 1930s,’ he wrote, ‘and went even further along the ascetic path by sticking almost exclusively to sansserif typefaces and a particularly noticeable form of grid composition.’

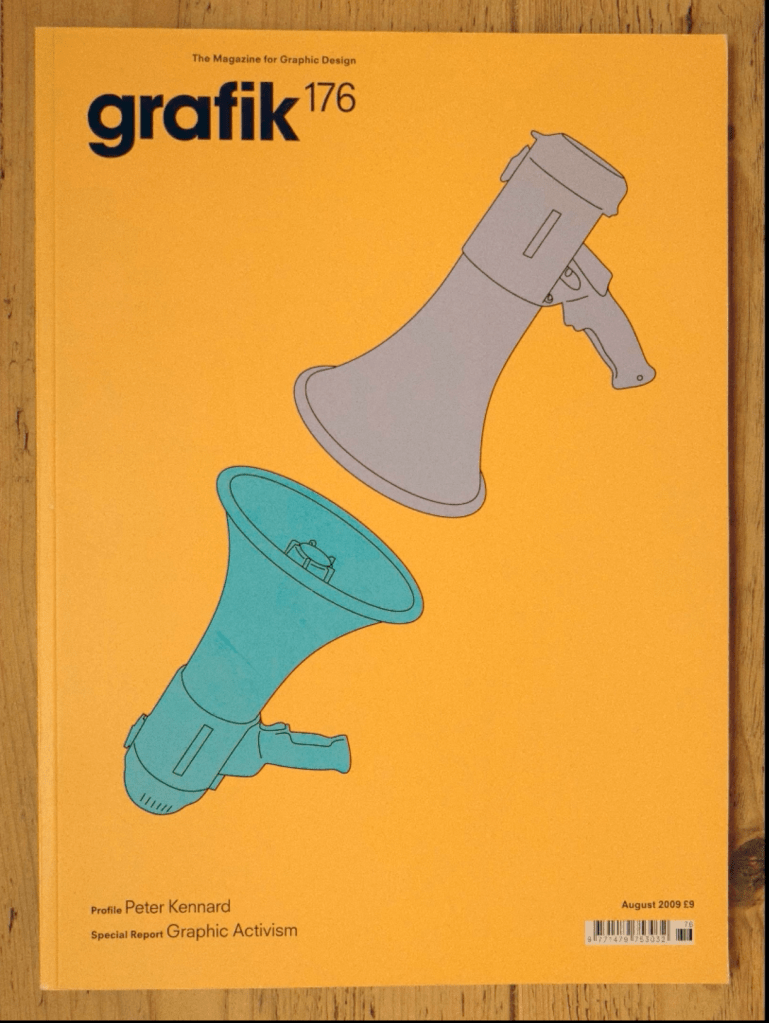

Most designers avoid making their political affiliations and sympathies public for fear of alienating clients. The graphic design profession over recent decades has been largely – though not exclusively – apolitical. Garland, on the other hand, never hid his political allegiances. And although it’s hard to say whether his commercial practice suffered because of this openness, perhaps in the 80s and 90s, when the design industry became the new best friend of big business, he might have missed out on a few lucrative commissions.

‘He was probably the only tutor we had who was also a working designer. And that was always exciting to us. It made a difference to our perception of him. And because he was only there for one day each week, he was more like a visitor. I can remember one of his projects, it was to make typographic hats, with a fashion show at the end of the day. He was always up for people having fun. He sometimes wrote the briefs backwards – he could do mirror writing with chalk on a blackboard. And he’d do things like stand on a table.’

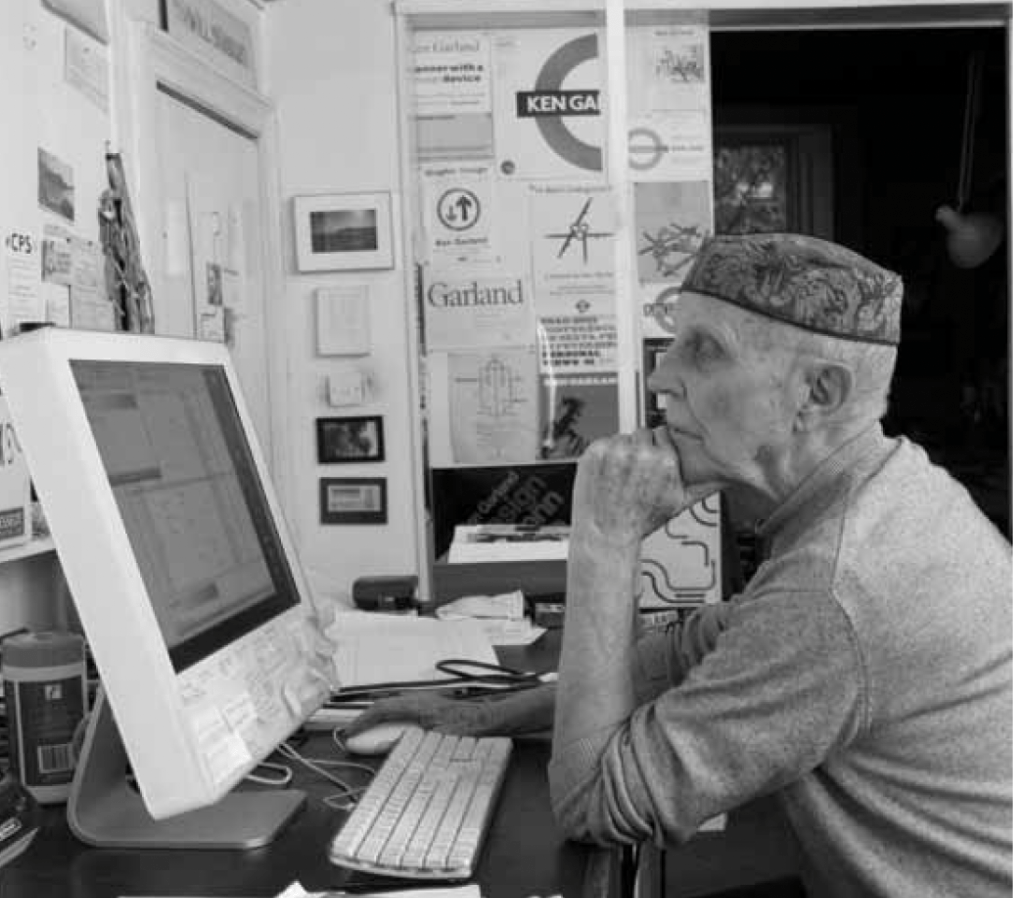

He lives quietly at home with his wife Wanda, in the house in North London that he has occupied and worked in since the 1960s. He lectures and travels (at the time of writing he has just returned from Poland and Spain), and spends most of his time writing, reading, taking photographs, and the occasional teaching assignment. Garland has a grown up son and daughter, and young grandchildren whom he devotes time to.

In coming to an assessment of Ken Garland as a graphic designer, it is necessary to stretch the definition of the term graphic design to its fullest extent. The mode of graphic design as practiced by Garland is the expanded version: he uses image and text to elucidate and inform; he has designed artefacts (for Galt Toys) that have enjoyed wide commercial success; he is also a commentator, a self-publisher and an educator. Yet perhaps this is graphic design in its truest form, and in fact, what other people call graphic design is really, in comparison, a contracted version.

Leave a comment