This week we will:

- Research a theme or social issue that raises questions connected to your locality.

- Analyse and evaluate methods of service design thinking and user-centred design processes, which help reveal issues about the group you are studying.

- Engage with local communities to identify issues that require design intervention.

- Deploy appropriate field-recording techniques and methods to help research and record information about your chosen theme.

- Collaborate through group discussion on the Ideas Wall.

Central to this proposition is the idea of engagement

How can designers engage local communities, groups of people or individuals, to help identify issues or challenges facing those local areas? How can designers amplify or explore more marginal voices and groups? How can we create opportunities for debate and discussion, and even how can we directly involve people in democratic or decision making processes themselves?

Hefin is a designer living in London and working across wider national and international localities. His design practice is grounded by situated approaches to research that draw upon discipline, such as sociology, pedagogy, craft and film making.

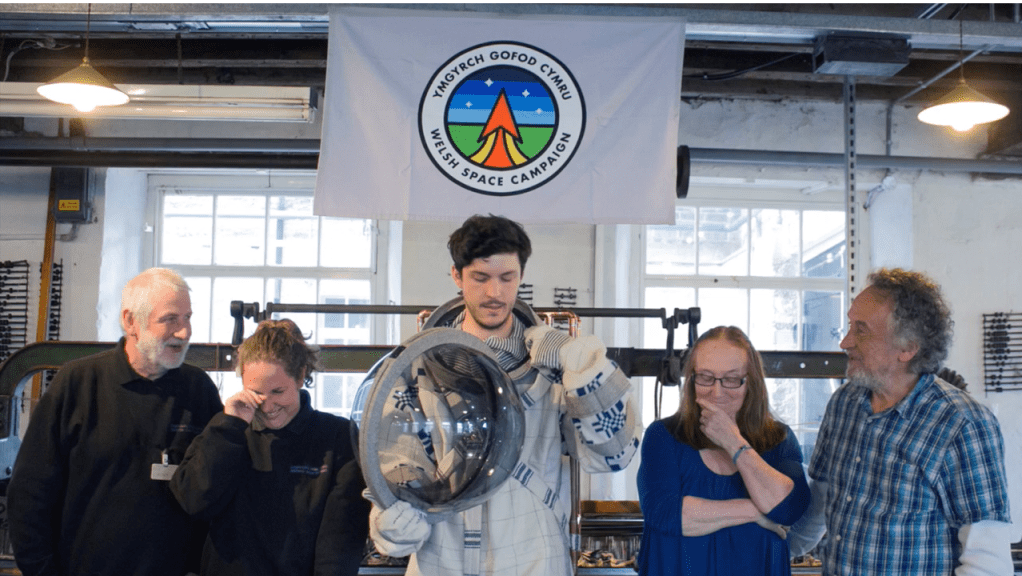

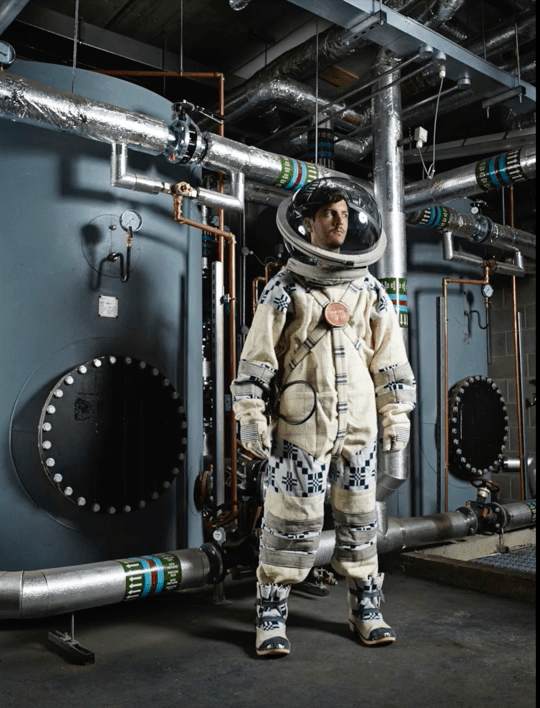

Welsh Space Campaign

“My actual experiences as being a service designer were very influential in terms of where I am now. However, there were I think very problematic elements, I found, in terms of working within service design. Specifically what was meant in terms of participation. And, actually perhaps that translated more into extraction. It often felt as though we were there, we were deployed, we plonked ourselves in an area very temporarily, we got what we needed to get and then we left.”

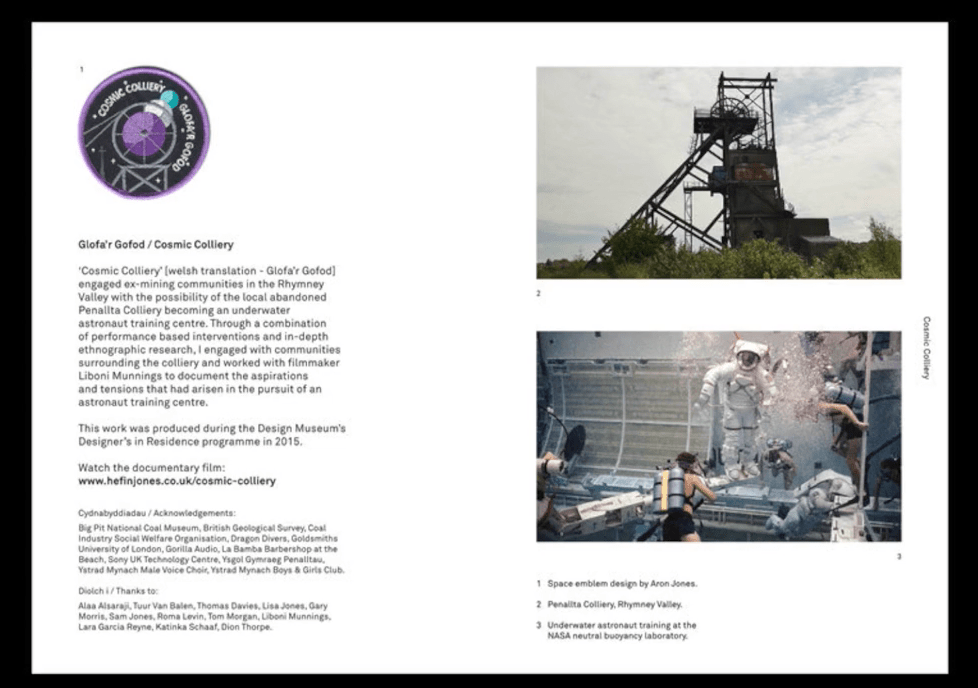

Cosmic Colliery project

The project is created in a very specific place with a very specific group of people.

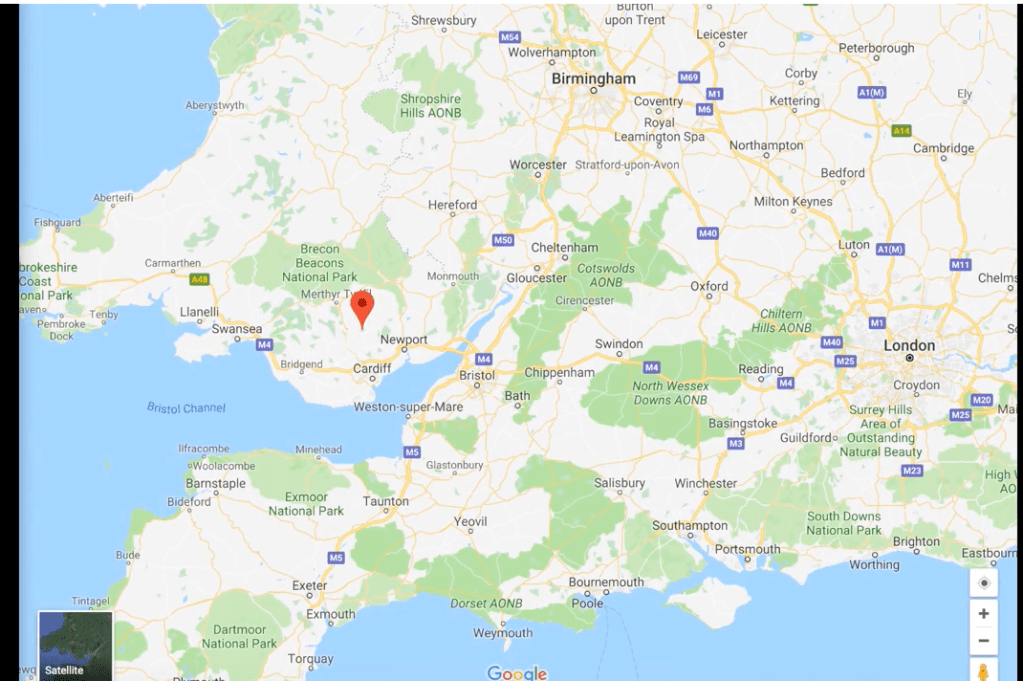

“Cosmic Colliery started with a proposal to a community in the Rhymney Valley of South Wales, specifically centring around a town called Ystrad Mynach. The proposal was to work with a group of people around that area to reimagine the abandoned coal mining industry there.

This area, I had some loose relationships to it; my parents and my brother and sister had grown up in a town nearby. I was also interested in it for lots of other reasons. For example, it was off the back of the last general election and the constituency it was in was one of the lowest turnouts in terms of voters and engagement in democratic, what is actually the main way we’re able to exercise our democracy. That was framed against lots of other things – it was the last coal mine to close in Britain. You had the Chartists, which was a working class movement in the 18th century that aimed to give rights to working class people. Many of the points of the charter are now national laws

There was a combination of different ways of working that were very much – and often with loads of other projects as well – they’re very much rooted in that place. There was a combination of things like going out and just spending time there; being there and expressing an interest to work together, but also allowing time to just be amongst the people that were working there. Spending time weekly with Ken, who’s the volunteer club leader at the youth centre, with a group of young people; allowing that process to really give rise to the questions.

One approach was to just spend time having long conversations with them around these things; creating a situation where we were all around a table having a conversation around certain issues. It wasn’t about my voice approving or disapproving certain things that were said, but being very much, there’s a person called Markus Miessen, he talks about this idea of a crossbencher – in the House of Lords you have the crossbenchers, people who aren’t affiliated, or aren’t supposed to be affiliated to either side. They sit in the middle. The idea is that you are someone in between that can provoke. You can ask the questions that either side might not.

I’ve done a lot of work within Wales and there’s a lot of things that allow me to do that work. We can look at it in terms of asking certain questions that sociologists, anthropologists ask. I think these are really important questions. How does, for example, the fact that I can speak Welsh, the fact that I am a man, the fact that I’m 9

white and have some affiliation to working class backgrounds – so all of these things – affect our access to a situation and the people’s relationships with that?

There’s another really good film called Two Laws, I think it is. It’s filmed by two people who had worked with an aboriginal community. Every single decision around the film and how they were telling the story was considered with that community. Within the specific community there has to be a caretaker present for the story – so that has to be someone, if you’re speaking, there always has to be someone present.

…Then also there’s an interesting thing around design which is, we don’t have ethics committees. That’s an interesting thing to think about in terms of there’s no one way of working. It comes back to this question of being responsible.

…I think my time growing up, working from 15 to 18 years old and maybe a bit later as a waiter, was probably one of the most important things in terms of how I learned to be around people and speak with them and have conversations and actually listen, taking orders. All of these things, I think, were separate in my head, maybe, to design. I then go into school and do this thing but actually all the time, all of these ways of being in the world, or these ways of giving care and being sensitive with things, I think that they become part of your capacity and your ability to just be in a situation and do stuff. “

Design Anthropology: Object Cultures in Transition

Clarke, Alison

Design Anthropology brings together leading international design theorists, consultants and anthropologists to explore the changing object culture of the 21st century.Decades ago, product designers used basic market research to fine-tune their designs for consumer success. Today the design process has been radically transformed, with the user center-stage in the design process. From design ethnography to culture probing, innovative designers are employing anthropological methods to elicit the meanings rather than the mere form and function of objects. This important volume provides a fascinating exploration of the issues facing the shapers of our increasingly complex material world. The text features case studies and investigations covering a diverse range of academic disciplines. From IKEA and anti-design to erotic twenty-first-century needlework and online interior decoration, the book positions itself at the intersections of design, anthropology, material culture, architecture, and sociology.

Twenty years ago, it was rare for designers to even talk with human and social scientist, never mind to employ their theories and methods. These days, it is not unusual to find psychologist and anthropologist among designers, sharing and adapting methods, integrating insights, generating and evolving ideas and implementing them. Many progressive organizations, ranging from Nokia to Nestle to the US center for Disease Control and Prevention, have embraced human centered design research in addressing business and social issues.

As a result, the practice of observing and interviewing people in their natural habitats has become widely established in design. So much so that nowadays it is the social sciences – with their focus on people, context, behavior, and subsequent insight about motivation and meaning – that largely dominate the conversation about how observation informs and inspires design.

But for design and designers there’s much more to observation than that. As we shall see, successful designers are keenly sensitive to particular aspects of what is going on around them, and these observations inform and inspire their work, often win subtle ways.

Like a critical moment. As businesses and organizations increasingly embrace design thinking and human-centered approaches, it feels important to understand more about how observation really works in design.

One can make good bets about fruitful activities” Let’s map thee competition, explore metaphors, interview extreme usurer, consider connotations of the brand, examine cultural context, visit the factory and salesroom, observes production processes.” But these activities, often build into ‘the design process’, are valuable to the extent that they inform and inspire the imagination of designers. Designers need to interpret what they see in ways that will lead to design outcomes. They need to make something of their observations, whether design strategies, principles, or concepts relevant to the project brief.

Design without both material and social impact in the world would not be design; designers must act in the sense that their outputs change thee facts on the ground.

“…The reasons an immigrant has for leaving a well-settled home are always varied, but a constant across those variations is the idea that the future could be different – at an individual level, but perhaps more importantly for many, the potential to bring change to thee world, to shift the ground, to alter the rules. It has been no different for us. Like many immigrants, we retain a good deal of where we come from in the ways that we think and in the values that we maintain, while at the same time trying to make as much out of the opportunities we came here to explore as we can.

Leave a comment