Ownership

“It is important to recognize that different countries and jurisdictions carry specific laws around intellectual property with regard to application and ownership.”

Lecture Podcast with Alec Dudson, Kevin Poulter, and Jonny Mayner.

https://www.freeths.co.uk/about-us/our-offices/london/

Kevin said “to avoid having to go through the time and cost and hassle of looking at that forensic detail, just simple documentary evidence, emails with dates, that sort of thing – when the documents were attached to those, as work-in-progress gets passed back and forth. Keep your emails, keep your documents, keep all your files nice and tidy so that if you ever do have to refer back to it you can, with as minimum fuss as possible….

The real problem now, or the real thing that people need to be aware of, is putting that information into the public domain so that it actually can be seen but then it can also be copied….

We’re talking about social media now on a global scale, which actually goes beyond what we call in legal terms, jurisdictional boundaries, you can’t limit where images will go on the internet and on social media. I think if we start, and this is the difficulty that the law has to deal with, how do we extend what the law says onto a global scale whilst also protecting individual jurisdictional rights? It’s very, very difficult to do….

The reality here is that, the more I look at it the more I suspect what probably happened with that case is that they’ve probably, on the quiet, entered into what we call a co-existence agreement, where they just say, look this is our mark, this is your mark, your mark is registered for x, y and z, we will register and use our mark for X, Y and Z and never the twain shall meet. And we’ll go about our business and never challenge each other ever again. They’ll sign up to a global co-existence agreement and everybody gets on with their day….

I think it’s also important to know what you are looking for? What are you seeking to achieve from this? If it’s about forcing a business into a position where they give in, whatever that might mean, what are you actually asking for? Because sending your army of Twitterati or Instagrammers after somebody, is going to get attention, of course it is, but actually what is it that you want? Do you want, as we said before, that collaboration? Do you want the payment? Do you want some sort of licence? Having a legal strategy around that is your primary focus or should be….

The difference between being an employee and being a freelancer can also be quite important particularly around things like ownership, but also in relation to protections that you have. Taking all of that information, making sure that you’re applying it in the right way. Understanding, most importantly, what you are responsible for, what you are liable for, but also the benefits that come with them. At the end of the day there are probably very few successful designers, artists, musicians, theatre producers, fashion designers, anything, who haven’t had a bad experience. ”

Jonny said that “the reality is that there’s not an awful lot that’s new under the sun. Someone out there may well have done something before you that looks a bit like that. Absolutely. If you’re putting your work out there on a global scale, there’s every chance that someone crawls out of the woodwork. That’s why it’s absolutely critical that you preserve and maintain your work-in-progress records, so that you’ve got your case for independent creation, your defence for independent creation, if anything does blow up.”

My takeaway of this podcast is that when we do a project, first thing is to do plenty of research. This way, we can find out what is out there, what is designed already in connection to our subject so, we avoid creating something similar and then creating bad situations. Second conclusion is to always record your process, keep the emails, or maybe organize everything in folders so, if is needed, you can find it quickly and proof that is your work.

https://www.thecut.com/2016/07/tuesday-bassen-on-her-work-being-copied-by-zara.html

https://www.designweek.co.uk/issues/15-21-january-2018/formula-1-face-legal-battle-new-logo/

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jul/30/tokyo-olympics-logo-plagiarism-row

1. Jacob, R., Alexander, D., Lane, L. (2003) A Guidebook to Intellectual property: patents, trade-marks, copyright and designs. London: Sweet and Maxwell.

“Copyright is principally designed to protect literary, artistic, and musical works, as well as other products of what may loosely be called the entertainment industry, films, sound recordings, broadcasts and the like. It arises automatically as soon as a work is physically recorded, without the need for any formalities, application or registration. (Some people think that ‘to copyright’ a work you have tO put © on it, but this is not so. But putting a © does serve as warning that the creator is copyright-savvy and may be the sort of person who knows how to sue.) Copyright does not play an important part in protecting industrial designs, though it once did. Copyright gives a.right to prevent copying. It does not give a complete monopoly in the sense that a patent does...Copyright in an artistic work arises when the work is made so that the owner of

The copyright gets immediate protection and there is no period of waiting for registration. In general, the period of copyright is the life of the author plus 70 years, but there are exceptions.…

A patent lasts – provided renewal fees are paid – for 20 years from the date of filing of the application at the Patent Office. Patent protection, however, does not become fully effective until the Office grants it, though once granted, damages can be claimed from the point at which the publication of the specification occurred (publication takes place 18 months after the date of application – which may be months, or even years, before a patent is granted).“

Here are some common examples of graphic design copyright infringement:

1. Using copyrighted images without permission:

- Image reproduction: Copying and using photographs, illustrations, or digital artwork in designs without obtaining a license or consent from the copyright holder is a common form of infringement.

- Examples: Using a stock photo without purchasing the appropriate license, or downloading an image from the internet and incorporating it into a design without permission.

I see many times logos that look alike – so is it a copy or is it because the designers had the same approach and ended with similar result (because after all, in how many way you can manipulate a letter – like the example with the Tokyo logo). For example when I saw the logo for the LP design (is a building company in Bulgaria), I knew I have seen it somewhere else before – the Leonardo Paper company – I see their trucks on the road all the time.

So, in this case what is it? Just a coincidence that the two designers came up with the same ideas or stealing the design?

Another example of similar logos are the Sofia airport logo and CNN:

Title: Guidebook to intellectual property pp. 21–26

Name of Author: Robin Jacob & Daniel Alexander & Matthew Fisher

Name of Publisher: Hart Publishing

The document discusses various forms of intellectual property protection, including patents, design rights, and copyright, particularly in the context of protecting new products and designs from imitation.

Copyright grants creators the right to prevent copying of their work. It does not provide a complete monopoly like a patent does, meaning others can create similar works independently without infringing copyright. Copyright protection arises automatically when a work is physically recorded, without the need for formal registration. For artistic works, the copyright lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years.

Patents and copyright

Patents and copyright differ in several key ways:

- Scope of Protection:

- Patents: Provide a monopoly over an invention, preventing others from making, using, or selling the patented product or process, even if they independently develop it.

- Copyright: Protects against copying of literary, artistic, musical, and entertainment works but does not prevent independent creation of similar works.

- Purpose:

- Patents: Designed to protect inventions that are new, useful, and non-obvious, such as industrial products or processes.

- Copyright: Focuses on creative works like books, films, music, and software.

- Registration:

- Patents: Require formal application and approval by a patent office, which can take time and involve fees.

- Copyright: Arises automatically when a work is recorded, without the need for registration.

- Duration:

- Patents: Last for 20 years from the filing date, provided renewal fees are paid.

- Copyright: Typically lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years.

- Monopoly vs. Copying:

- Patents: Grant a complete monopoly over the invention.

- Copyright: Only prevents copying, not independent creation of similar works.

These differences make patents more suitable for protecting inventions and industrial designs, while copyright is ideal for creative and artistic works.”

Title: Guidebook to intellectual property pp. 141–146

Name of Author: Robin Jacob & Daniel Alexander & Matthew Fisher

Name of Publisher: Hart Publishing

Copyright law

“The document identifies the following main functions of copyright law:

- Protection of Creative Efforts: Copyright law protects the fruits of a person’s effort, labor, skill, or taste from exploitation by others.

- Negative Rights: It provides negative rights, meaning it prevents others from doing certain things (e.g., reproducing or copying a work) without the copyright owner’s consent.

- Distinction Between Ideas and Works: Copyright protects the expression of ideas (e.g., a photograph or painting) rather than the ideas themselves.

- Legal Foundation for Transactions: Copyright law provides a legal basis for transactions in rights, such as remunerating creators when their work is used commercially (e.g., music in films or on radio).

- Supplementary Protection: Copyright can serve as an additional tool to protect confidences or commercial interests, such as preventing unauthorized copying of business letters or advertising brochures.

- Encouragement of Creativity: By ensuring creators can benefit from their work, copyright law incentivizes the creation of new works.

- Piracy of Substantial Works: These are rare cases where significant works, such as computer programs or films, are pirated for their intrinsic value.

- Ulterior Commercial Reasons: Disputes arise when the original work has little intrinsic value or is not reproduced in a conventional sense, but copyright is invoked for commercial purposes.

- Disputes Over Works with Goodwill Value: These involve works that embody significant skill or labor (e.g., fixture lists or timetables) but derive their value more from goodwill than the effort invested in them. These cases often involve arguments about whether copyright law applies.

These functions collectively aim to balance the rights of creators with the interests of users and society.”

“The first real Copyright Act, the Statute of Anne 1709, gave authors of books the sole right and liberty of printing them for a term of 14 years. ‘Books and other writings’ were held to include musical compositions (Bach v Longman, 1777) and

dramatic compositions (Starace v Longman, 1788). In the former case JC Bach sued the publishers for reproducing harpsichord and viol di gamba sonatas. Lord

Mansfield said: ‘A person may use the copy by playing it; but he has no right to rob the author of the profit by multiplying copies and disposing of them to his own use.’ This is an early instance of a recurring theme in copyright law: if something is worth copying, it is worth protecting. That principle has heavily influenced the courts and Parliament for the last 200 years.

The document outlines the following common types of copyright disputes:

These disputes highlight the varying contexts in which copyright law is applied, ranging from straightforward piracy to more complex commercial and goodwill-related issues. ”

Title: Guidebook to intellectual property pp. 155–160

Name of Author: Robin Jacob & Daniel Alexander & Matthew Fisher

Name of Publisher: Hart Publishing

Employee status and copyright ownership

Employee status significantly affects copyright ownership. If a literary, dramatic, musical, artistic work, or film is created by an employee in the course of their employment, the copyright automatically belongs to the employer, unless there is an agreement stating otherwise. This rule applies only to employees working under a “contract of service” and does not extend to independent contractors or individuals loosely described as being “employed to produce the work.”

For example:

- An architect employed to design a house retains copyright in their design, but an architectural draughtsman working for a salary transfers copyright ownership to their employer.

- If an employee creates a work outside their job duties or during their spare time (e.g., a translation done for extra payment), the copyright may belong to the employee, as seen in Byrne v Statist (1914).

The phrase “in the course of his employment” can be complex and has led to litigation, but generally, it means the employee was hired to produce the work as part of their job duties.

If an image is created by AI who has the rights?

Determining legal rights and ownership of AI-generated images is a complex and evolving issue. Currently, in the United States, AI-generated images alone are not eligible for copyright protection because copyright law requires human authorship.

Here’s why and what that means for legal rights:

- Human Authorship Required: US copyright law is based on the principle that creative works must have a human author to be eligible for protection. AI systems are not considered legal entities capable of authorship.

- Public Domain Status: Since AI-generated images lack a recognized human author, they are generally considered to be in the public domain by default in the US. This means that no one can claim exclusive copyright ownership over them.

- The User’s Role: While some argue that the human who provides the prompts or inputs to the AI should have ownership rights, the US Copyright Office has clarified that if the “traditional elements of authorship” were produced by the AI, it lacks human authorship and won’t be registered for copyright.

- Human-AI Collaboration Exception: There can be exceptions if a human provides significant creative input to the AI-generated image. For example, if a human significantly modifies or customizes the AI-generated image or creatively arranges AI-generated elements, the work may be eligible for copyright protection, but only for the human-authored aspects.

- AI Tool Terms of Service: While you may not be able to copyright the raw AI-generated image itself, AI platforms may grant users rights to use the images they create. These terms can vary, so it’s important to understand the platform’s policies before using AI-generated images, especially for commercial purposes.

In summary:

- Purely AI-generated images are generally not copyrightable in the US because they lack human authorship.

- They may be considered in the public domain, meaning no one can claim exclusive ownership.

- Human input and creativity can lead to copyright protection for the human-authored elements of a work that includes AI-generated content.

- AI platform terms of service may grant users specific usage rights for AI-generated images, even if they aren’t copyrightable. “

https://www.scoredetect.com/blog/posts/can-you-copyright-ai-art-legal-insights

“At present, the U.S. Copyright Office does not consider AI systems to be authors, as they are not human. So under current copyright law, raw AI-generated content falls into the public domain by default.

However, this landscape may evolve as AI capabilities advance. There are pending lawsuits and Supreme Court decisions that could set new precedents. Additionally, lawmakers are considering an AI Act that defines parameters around IP rights for AI output.

For now, while individuals or companies cannot copyright raw AI art, they may claim rights by adding original creative elements. But requirements are strict, with only minimal edits allowed before it’s considered derivative work.

So AI art ownership remains complex. We’ll likely see new legislation and case law that shapes how copyright applies to creative AI over time. Those using these models should stay updated on legal developments impacting their work.”

Work on Project 1

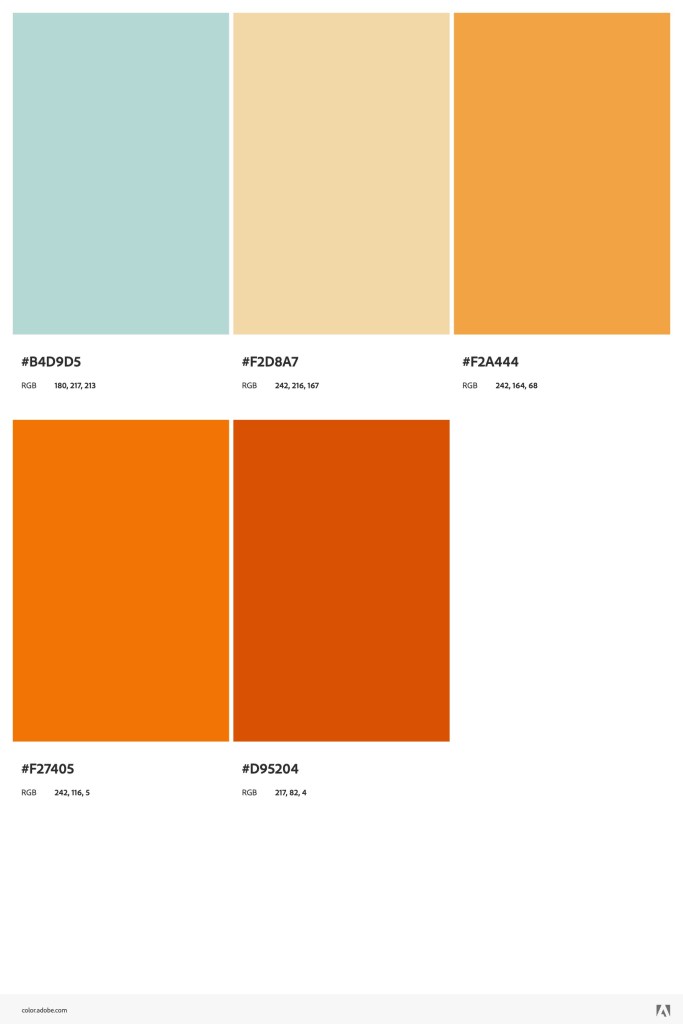

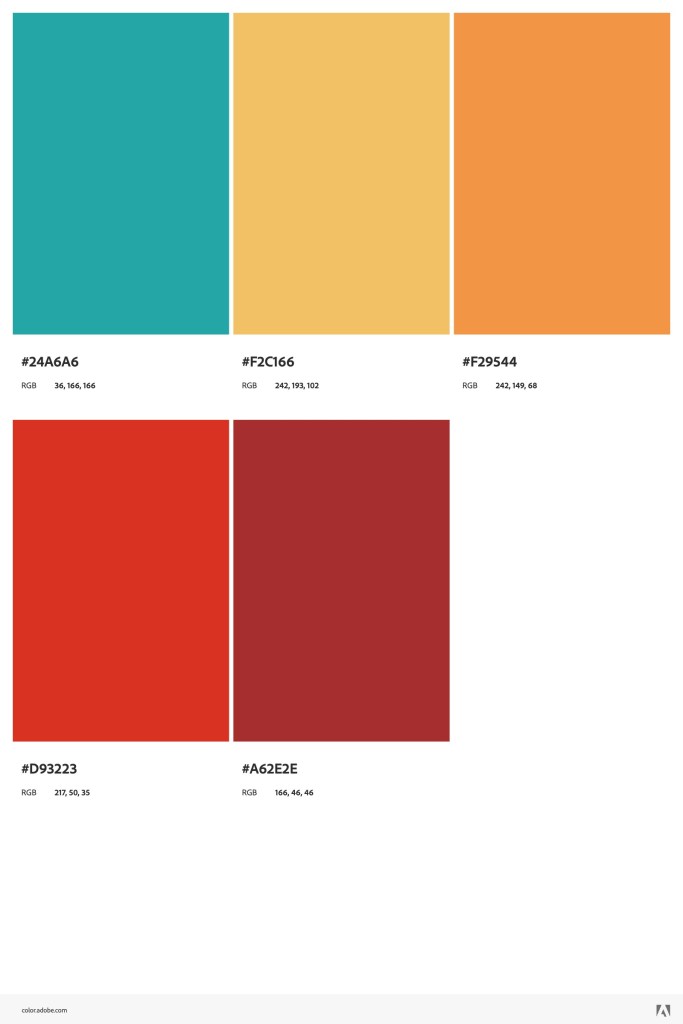

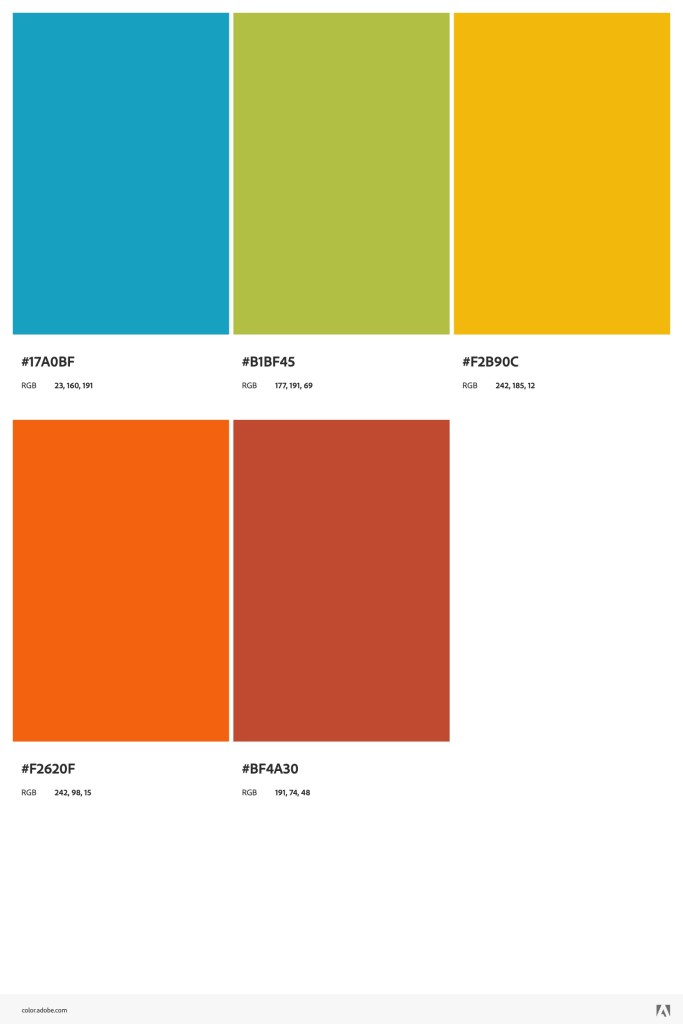

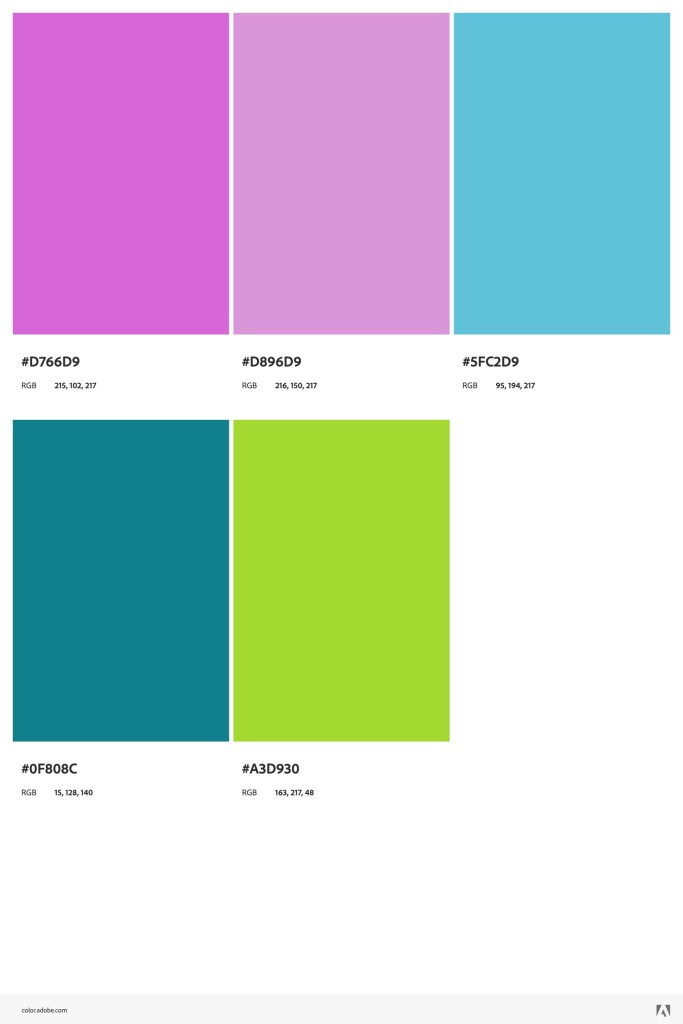

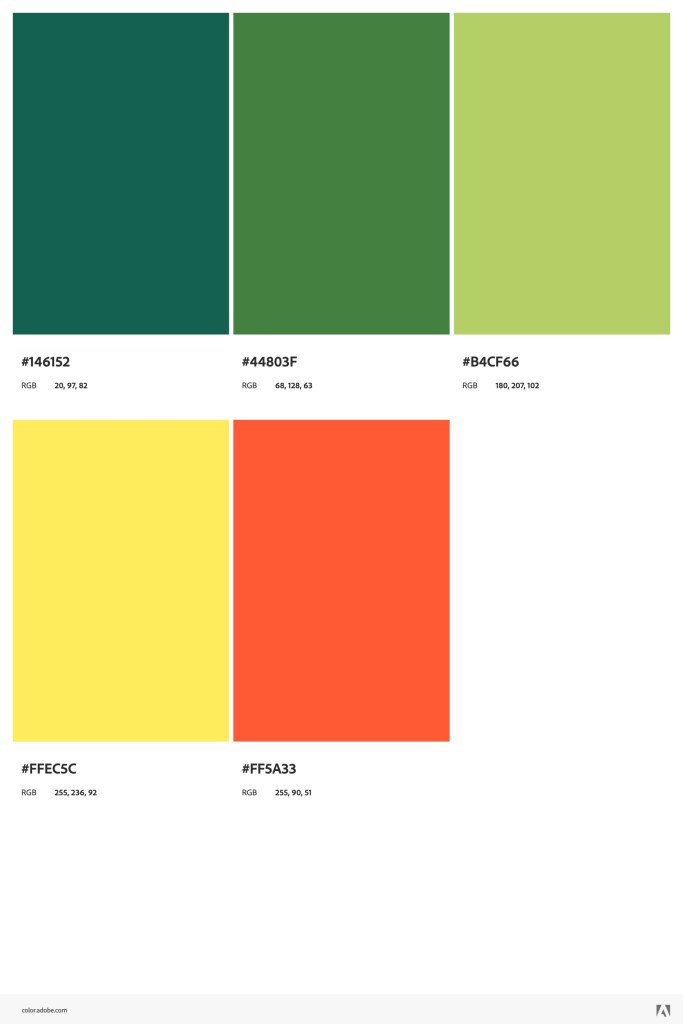

Before I go back to work on the framework and the content, I want to choose color palette.

I think if I use too many colors is going to look confusing. Maybe I should stick with just couple colors.

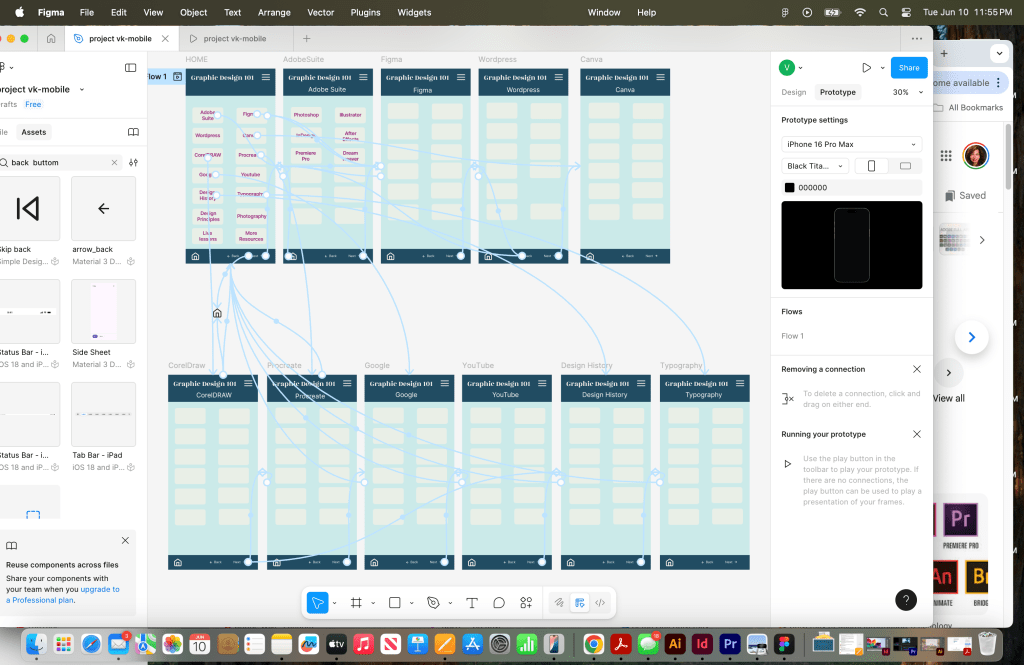

So, here couple pages:

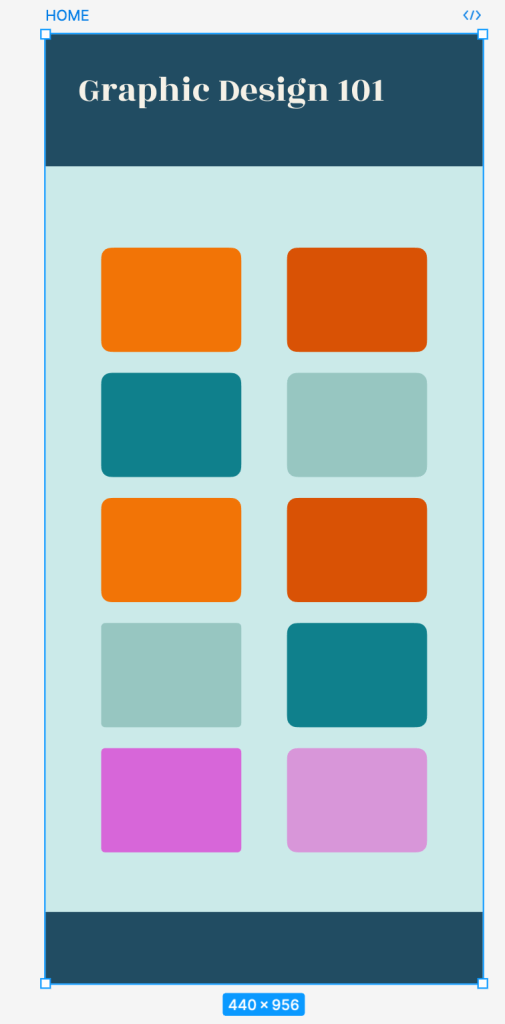

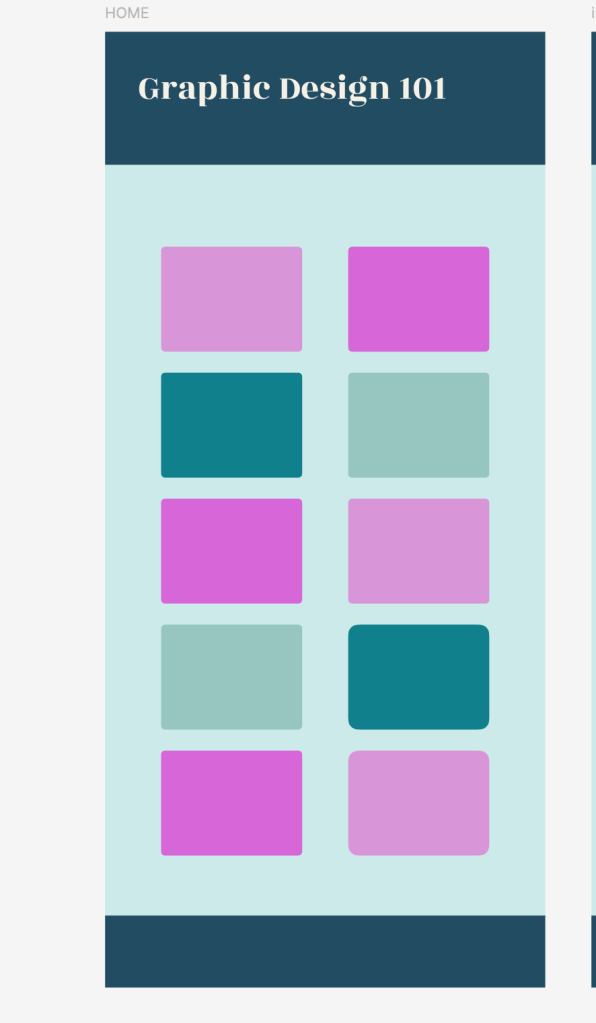

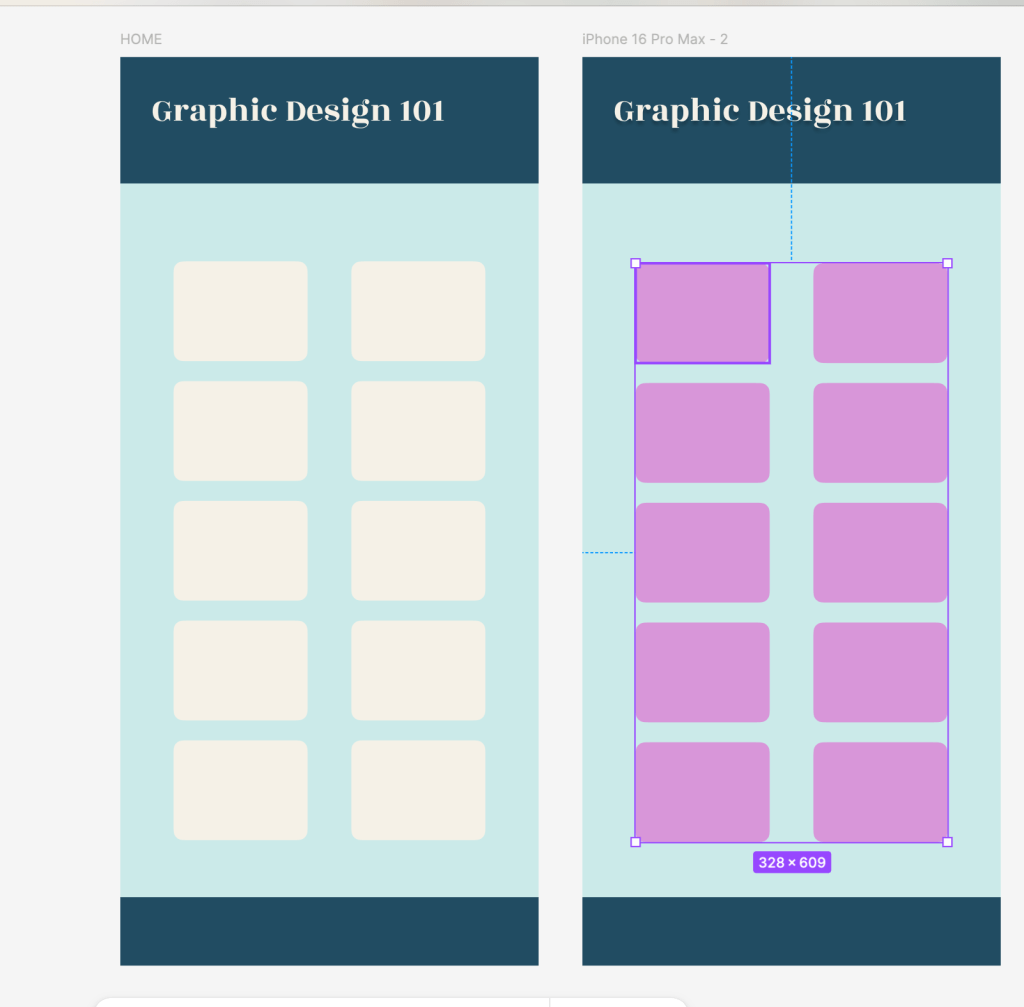

Still working with the organization of the site (this is mobile version).

I think I will go first with the desktop version